Metaphysics Resurrected

Month long focus on the history of metaphysics with philosopher Dylan Shaul

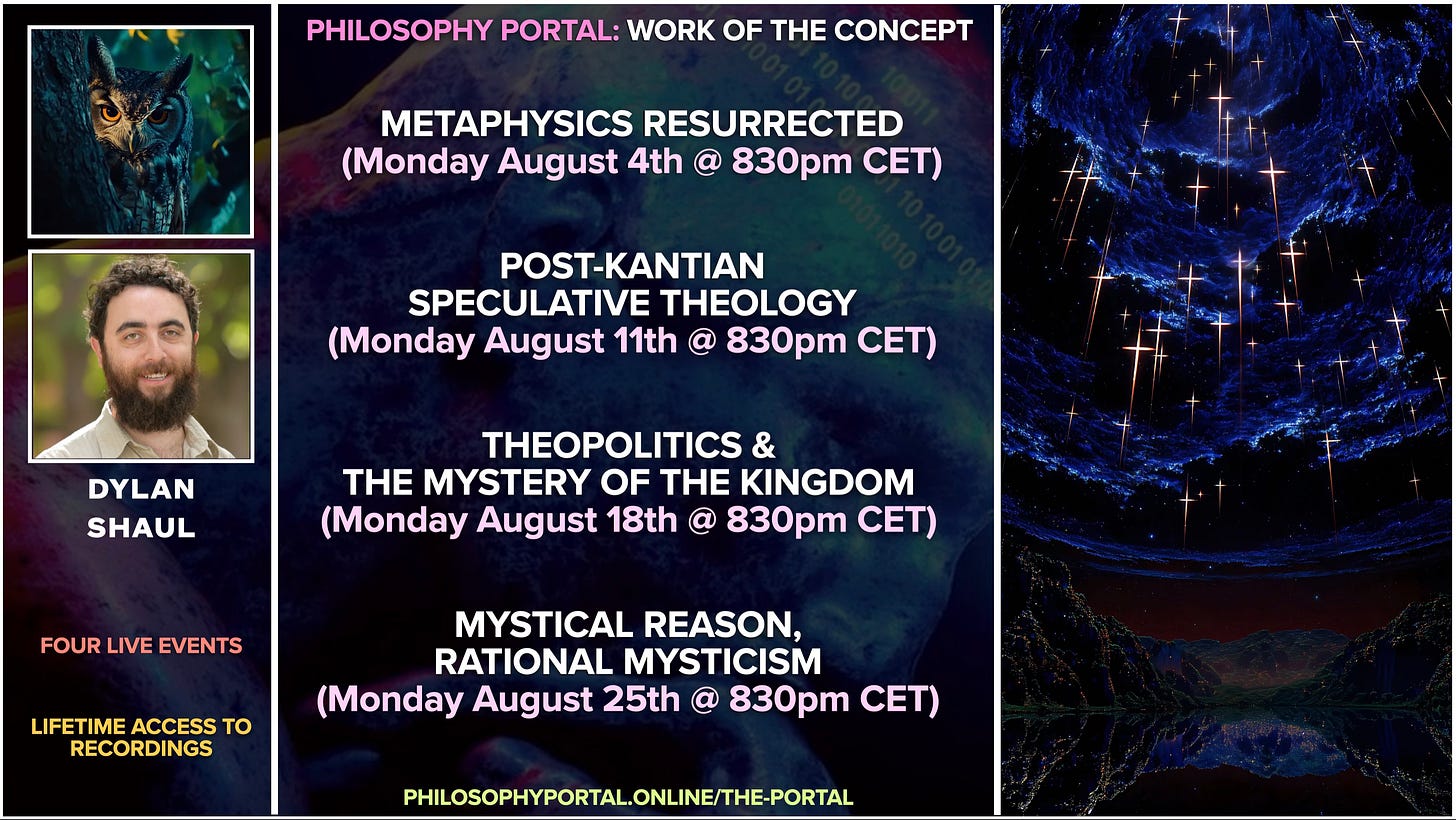

This August at The Portal we host philosopher Dylan Shaul for a series of reflections under the theme of “Metaphysics Resurrected”. Throughout this month you are invited to four events designed to introduce you to the history of metaphysics, including: the core of the metaphysical tradition, from Plato to Leibniz, the Kantian turn opening us to a post-metaphysical universe, the possible return of metaphysics in contemporary philosophy, as well as reflections on the relation of pure reason and mystical knowing. The entire schedule can be found below:

To get involved, you can either sign up as a member of The Portal, which gives you access to the entire history of our recordings, as well as four live events every month, and discounts on past/future courses; or you can sign up for the month as a stand alone mini-course, giving you access to all four live events, as well as lifetime access to the recordings. Find out more below:

In order to prepare for this month, I hosted a conversation with Shaul to reflect on many of the themes that we hope to explore more fully throughout August. You can find that conversation below:

What you can find below are some general themes that we hope to expand on in the mini-course:

Metaphysics in General

Metaphysics in general is the science of causes, and a cause is any reason or explanation for some caused thing (e.g. material, efficient, formal, final). We exist in a world of causes. We ask, simply: why? Why are things the way they are? Why are things not some other way?

For Shaul, the key is that we can do that both backwards and forwards: backwards into the first cause or primary beginning of all things, and forwards until you reach some final cause or end of all things as the purpose.

Traditionally, in the Platonic tradition, the only good candidate for first and final cause is God. God is here traditionally associated with “The Good”: both The Good that gives rise to all beings/existence itself, and The Good towards which all things are striving, and which in the human universe becomes an ethical political ideal.

For Shaul, this system encapsulates the metaphysical tradition from Plato to Leibniz, and provides us with the structure for orienting humans collectively.

Grand Narratives

Metaphysics is not only about the absolute and eternal divine cause and end of all things, it is also the belief that pure reason can come to know the absolute and eternal divine cause and end of all things.

The three traditional objects that metaphysics claims to know through pure reason are “God, Soul, and World”. This triad forms the basis for both the absolute first and final cause (God), our being and mind in relation to that cause (Soul), as well as the container or stage on which we dramatise our origin and orient our end (World).

From the critical philosophy of Kant onwards, however, there is the idea that we need to, through the critique of pure reason, abandon metaphysics, its structure and its project: we cannot know God, Soul and World. For Kant, God, Soul, and World are “noumenal” (unknowable through pure reason). This tradition has intensified in various forms that we could call “the death of metaphysics” or even “the death of God”.

For Shaul, he asks: have we exhausted this critical field as a whole? Does 20th century philosophy demonstrate that we were perhaps mistaken to think we can get rid of metaphysics, its structure and its project? Has the end of metaphysics come to an end? Do we need to return to a new beginning of the metaphysical tradition? If so, how would one revive the tradition and structure from Plato to Leibniz? Can we revive metaphysics while also incorporating the justified criticisms of 19th and 20th century philosophy?

Kantian Turn

While there have always been critics of metaphysics (e.g. sophists, materialists, nominalists, skeptics, empiricists), Kant was the first to critique metaphysics on its own terms: pure reason. Kant is the first to argue against metaphysics in the name of pure reason itself. For Shaul, we might consider this the “euthanasia of pure reason”, i.e. pure reason destroys itself in its own thinking.

The philosophical revolution of Kantian philosophy here mirrors the social revolutions of his time: the French and American Revolutions, respectively. While political revolutions were concerned with killing the king, Kant killed the reason that justified the metaphysical position of the king (e.g. “Divine Right of Kings”). Through these revolutions the metaphysical systems orienting the collective social substance to “The Good” were replaced with the human mind and freedom as the absolute.

Today we are living in the wake of these social and philosophical revolutions. They of course have much to offer (e.g. individual rights, free speech), but also have many problems (e.g. what is our freedom for?). How can we think the relation between the ancient metaphysical systems orienting towards The Good (often under divine presuppositions of a heavenly hierarchy), and modern notions of freedom (liberty, equality)?

Today, discussions in this direction are often framed under the banner of “post-liberalism”, i.e. the exhaustion of liberalism, and the need for a higher order principle that does not simply leave us in a flat individualism. Throughout modernity, the signifiers communism and fascism have most notably been associated with that turn, but in the disappointment and failures of those projects, many ask: what about returning to Platonic metaphysics?

Liberalism and Platonism

For Shaul, the problem with liberalism is that it doesn’t endorse any particular vision of The Good life, it doesn't think of politics as pursuing The Good. Rather, liberalism creates a neutral procedural formal space where each individual or group of individuals can pursue their own concept of The Good life in freedom without interference from other human beings. What is good to one may not be for the other, and thus not an absolute orienting the human collective as a totality.

Shaul warns us that Plato and Aristotle alike may worry about that project, as it could lead to nihilism. Indeed, it is well known that the history of modern liberal project has cast the shadow of nihilism, or always seems haunted by its possibility. Is this because we don’t have a collective vision of The Good life? Is it because each man is as an individual the “measure of all things”? Are we doomed to nihilism without a political collective that endorses a species notion of The Good?

In Shaul’s work, he link the Platonic tradition to the Judaic tradition in the idea of the Kingdom of God. What is called the absolute and eternal Good is God, and in that frame, God is king. The principle: no man can be a king over any other, only God can be king. For Shaul, this is an ideal political system that both frames God as the divine shepherd over humanity, but among humans, leaves us to our freedom and equality. Here Shaul asks us: is this political view realisable without divine intervention?

We know what Christianity has to say about that.

But what about modern liberalism? Does it not presuppose that we can realise freedom and equality without God at all?

We know what the 20th century has to say about that.

Here we are left to face many questions.

Liberalism as Void

The furthest extremes of anti-metaphysical thinking terminates in a political vision of democracy as the absence of Truth, and the absence of The Good, in absolute and eternal form. For example, in the philosophy of democratic materialism we find only bodies and languages, and no absolute Truths or The Good. Shaul asks us to consider Jacques Derrida’s “democracy to come” which uses deconstruction to license a form of government that can constantly undo itself, to rethink and re-reflect on itself. Or consider Richard Rorty’s pragmatic democracy which frames democracy as the open space of contestation without an overriding Good or Truth to be the final arbiter of ethical determination.

In contrast, more recent forms of dialectical materialism add to the mix of bodies and languages, the Truth, but in a non-idealist form, and often in a non-democratic form. Consider a figure like Alain Badiou who suggests that the democracy of bodies and languages needs to be supplemented with Truth-Events: we decide upon a The Good life through fidelity to a Truth-Event. Here consider radical breaks in history like the French, American or Russian Revolutions: these Truth-Events either become The Good or the bad in relation to our fidelity to their historical opening. Or consider a figure like Slavoj Žižek, who thinks the Truth in the form of an abyssal act, a tarrying with negativity; and in the context of liberal politics, do we find a notion of “The Good” in orientation towards some form of negative (“War”) Communism?

For Shaul, what both the democratic and dialectical materialist approaches to Truth and The Good miss is that they are just opening us to more and more void. Shaul again asks us to think from the standpoint of a neo-Platonist: what is the ground of liberalism? Is it negativity and void all the way down? Have we considered the possibility that materialism needs to be supplemented with an immaterial/ideal notion of The Good as the highest principle? Here material is conceived as secondary to, not the void, but The Good. As we covered above, this turns out to be life under kingship of God.

Platonic Political Myth

Shaul reminds us that Plato frames a political narrative, a story about the ideal human organisation, that articulates an original Golden Age where The Goods (universal justice, peace, harmony, happiness) were realised. However, in this story, we fell from this ideal, and we now find ourselves in a degradation from The Good: we are without rudder and steersman. In this story, we are without direction and in degradation until the point of total destruction, where oars will be taken up, and proper orientation will be rediscovered towards a future Golden Age, where we re-realise “The Goods”: universal justice, peace, harmony, happiness.

How is this possible? Shaul tells us that Plato and Aristotle both teach us that all human beings desire The Good, and that no one desires the bad. The problem in human civilisation is that humans start to equate The Good with wealth, power, fame, and pleasure as ends in themselves, as opposed to possible means towards The Good. For Plato and Aristotle, nothing can ultimately satisfy human beings: not wealth, power, fame or pleasure, except God who is the ultimate Good.

How does this work in practice? For Shaul, he speaks for the ethics of divine imitation: just as God is perfectly just and wise, we should strive to be perfectly just and wise. Without divine imitation, we fall into manly imitation, and start striving for wealth, power, fame or pleasure, and thus sacrifice the happiness of unity with the divine and eternal absolute, for a temporary satisfaction in secular worldly pleasure.

The practical political challenge for a neoPlatonist is something like: is collective realisation and embodiment of divine imitation possible? Can we bring heaven to earth? Can we achieve both inner and outer peace and restore the Golden Age in Plato’s political myth? Alternatively, for the Platonist, are we doomed to an eternal liberal degradation without righting the ship?

Modern to Ancient Return?

Shaul is sometimes asked: is your neoPlatonist project nothing but a return to the ancient and an obfuscation of the modern? Is all value in the ancient, and is there no value in the modern?

Shaul’s response is that there is a confusion between the ancient and the modern on the level of freedom and The Good. While the modern puts freedom as its absolute, as an end in itself (subordinating The Good to a relativity); the ancient puts The Good as an end in itself (subordinate freedom to a relativity). He notes that the performative contradiction for the modern subject is that, while thinking of freedom as the absolute, many still believe that freedom should be constrained in relation to Evil. Moreover, many still believe that this constraint is not just for The Good of society, but also for The Good of that individual, because through Evil, we damage both the social and our individual soul.

Shaul also notes that the modern subject can learn something general from the ancient metaphysics of The Good: that while one is free to pursue wealth, fame, power, and pleasure, that all of these freedoms can be used for either Good or Evil. But what is the only thing that can be used for good? The Good.

While Shaul notes that this argument is a tautology, and that much of philosophy seems to find itself in tautology, he maintains that without at least an attempt to salvage the core of the ancient philosophical perspective, we head into the future without a real aim and orientation.

If you are also thinking about these questions, join us this August in The Portal.

It's great that Shaul will be in The Portal next month, and this article frames well the problems and stakes we need to think. Looking forward to it!