Metaphysics Resurrected (Part 2)

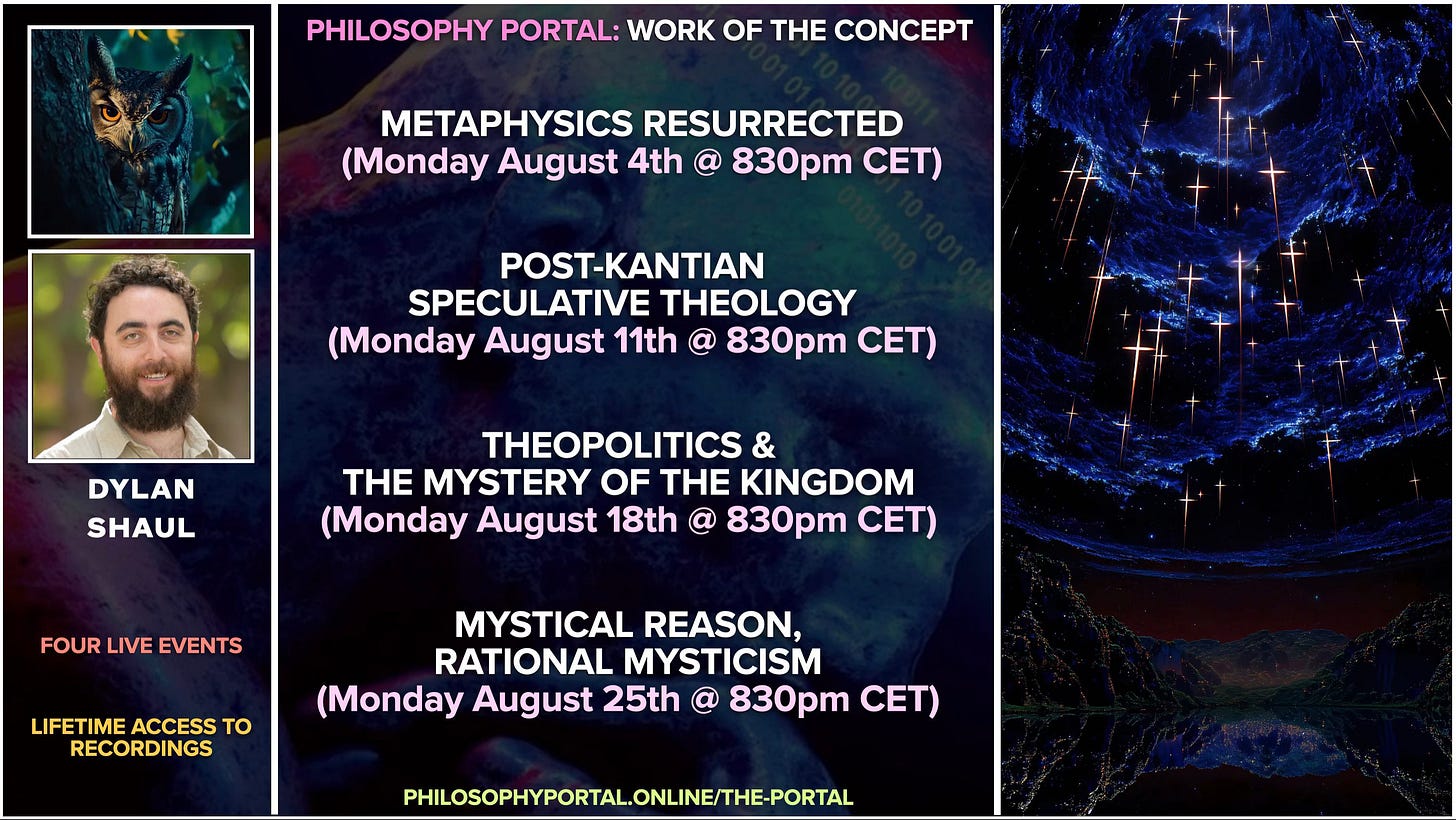

Month long focus on the history of metaphysics with philosopher Dylan Shaul

This August at The Portal we host philosopher Dylan Shaul for a series of reflections under the theme of “Metaphysics Resurrected”. Throughout this month you are invited to four events designed to introduce you to the history of metaphysics, including: the core of the metaphysical tradition, from Plato to Leibniz, the Kantian turn opening us to a post-metaphysical universe, the possible return of metaphysics in contemporary philosophy, as well as reflections on the relation of pure reason and mystical knowing. The entire schedule can be found below:

To get involved, you can either sign up as a member of The Portal, which gives you access to the entire history of our recordings, as well as four live events every month, and discounts on past/future courses; or you can sign up for the month as a stand alone mini-course, giving you access to all four live events, as well as lifetime access to the recordings. Find out more below:

In order to prepare for this month, I hosted a second conversation with Shaul, as well as Dimitri Crooijmans of

and Daniel Coughlan of , to reflect on many of the themes that we hope to explore more fully throughout August. You can find that conversation below:What you can find below are some general themes that we hope to expand on in the course:

The Negation of the Negation (Affirmation) of Metaphysics

Throughout the course we will be exploring the “positive history of the metaphysical tradition”, including Plato, Aristotle, Neo-Platonists, Medieval Scholastics, and the Modern Rationalists; the “critique of metaphysics” from the works of Immanuel Kant and the German Idealists onwards; and also the possibility that we are either within or are in the process of realising a renewal/resurrection of metaphysics that results from the exhaustion of its negation (it is possible, to come).

Special Metaphysics

Metaphysics as the study/sciences of causes can be split into two major branches: general metaphysics, or the study of being/ontology; and special metaphysics, which can itself be divided into three branches: rational cosmology, or the science of the world; rational psychology, or the science of the soul; and rational theology, or the science of god. These three branches will dominate our focus in this course, with special attention to their “unconditioned” nature. Here we will position the positive history of metaphysics (e.g. Plato, Aristotle, Neo-Platonism, Medieval Scholastics, Modern Rationalists) as the support for special metaphysics, and the Kantian critique as its deconstruction as “transcendental illusion” (e.g. world, soul, god).

Political Ideals

The positive history of metaphysics has political consequences in concepts that we have come to see only in the form of transcendental illusion, but which perhaps require a new re-assessment: “Kingdom of God” and “Heaven on Earth”. The Kingdom of God proposes the idea that only God is King, which in its negation means that: no human can be king over any other. The idea of Heaven on Earth is inspired by “God as the Good”, and the highest “Good” as “universal peace” for all human beings. Combined, the political ideals of the “Kingdom of God” and “Heaven on Earth” form the basis for the striving, imitation and embodiment that classical metaphysics instantiates. Should these ideals be critiqued? Should these ideals be resurrected?

What About Critique?

This course is not just a “return” to the “positive tradition of metaphysics”, but rather also trying to raise metaphysics inclusive of its negation and critique. This means that we cannot just go back to the basic presupposition of the positive tradition of metaphysics as if the critique did not happen. Any raising of the positive tradition of metaphysics must be done inclusive of the truth of its negation and critique. Here some questions that come to mind include: did the positive tradition of metaphysics already have its critical break internal to itself (e.g. sophists, materialists, empiricists, nominalists, skeptics), or even in figures like Descartes, who started to theorise the cogito under the paradigm of self-doubt. Perhaps more importantly, can the positive history of metaphysics withstand not only Kant’s “critique of pure reason”, but also the psychoanalytic break with “death drive”, or the “critique of pure desire”, which forces us to consider a dimension that goes beyond both idealisation and sublation?

Metaphysics and Judeo-Christianity

The positive tradition of metaphysics was grounded in a notion of the absolute and eternity that is separate, above the fray, of history and time. For the positive tradition of metaphysics, to bring the absolute and eternity into history and time, is to be allowing for an inclusion that necessarily leads to the degradation of our notion of both the absolute and eternity. This positive tradition is complicated by the theology of both Judaism and Christianity in different ways, considering that both traditions introduce a complicated social drama of eternity and the absolute that necessarily includes a relation between absolute and eternity and history and time. In Judaism the absolutely eternal seeds the possibility for its own personalisation, and in Christianity this possibility is realised in the figure of Christ, which brings us to face the absolute coincidence between eternity and historical time. How does this change philosophy? What philosophies are impossible given these theologies? How does one’s theology change one’s relation to philosophy?

These questions will be with us throughout August. To sign up:

A very intriguing course of study, but what I don’t see and haven’t seen is discussion of a positive metaphysics not based on the (often and almost entirely unquestioned) assumption of an independently existing God, Being, One, Substance, etc. To me, this is extremely fertile, groundless ground.