Phenomenological Turn

Hegel's Science of Logic (2)

The second video in a series preparing for a Science of Logic course starting January 16th 2023 focuses on Hegel’s “Phenomenological Turn” in 1807. For the first, see: Formative Moments.

Hegel’s phenomenological turn signals the moment where he decides to release one of his greatest works, the Phenomenology of Spirit, before releasing his Science of Logic. The reason for this turn involves key breaks with his philosophical contemporaries, Johann Fichte and Friedrich Schelling, and marked a passage that Hegel thought was necessary to introduce before realising his logic.

In order to fully understand this turn, let’s start with the release of the Phenomenology of Spirit. This book was Hegel’s attempt at a science of experience, which is importantly not focused on any external phenomena, like physics or chemistry, but rather focused on the concept of what consciousness makes of itself, its own existence, in the development of its self-notion. Here to fully understand Hegel, one must always remember that external phenomena are always understood from within the becoming of the self-notion, as a part of its own self-mediation. For Hegel, there is no “physics” or “chemistry” independent of the self-notion (they are the way Nature appears “for us”). And while there is a “Nature” independent of self-mediation, this Nature does not possess an inner intelligibility independent of the self-notion.

In the Phenomenology, Hegel develops his science of experience by way of a journey or an adventure, where the logic of spirit’s experience unfolds from sense-immediacy (like sensing a “this” or a “that” as fleeting presences), to absolute knowing, where the self holds itself in an infinite recursion or strange loop. This strange loop is nothing but its own becoming-other to what it is immediately via notional mediation, but in the same way, it is paradoxically self-similar in this eternal difference. The point here is that Hegel wanted his readership to understand the process by which a “child” becomes “knower,” before entertaining his arguments in the science of logic. He wanted his readership to understand in detail, how conscious experience moves through a series of forms, experienced in their negativity and contradiction, before establishing for itself a true knowledge of self.

In some sense, it is not an over-simplification to say that Hegel’s entire “phenomenological turn” involves a new development in his relation to the concept of intuition. Hegel’s philosophy gained its own footing in viewing the function of the intuition as problematic, and as a metaphysical enemy to the true unfolding of reason. This differentiation emerges primarily in relation to Friedrich Schelling’s work. For Schelling, one could intuit the Absolute, an idea that he develops in relation to artistic expression (which he places on a higher order than philosophy). For Hegel, this immediacy of intuition prevented consciousness from making sense of itself conceptually, and figuring out what it is as a result or a mediation of a process (like a true knower), as opposed to its simple immediacy (like a child). In this sense, Hegel is basically saying that the pre-Hegelian philosophies are “child-like” in comparison to his work, which is a “matured form” of philosophy.

From this idea on the split between intuition and concept, Hegel suggests we must think two series of consciousness, one ordinary, the other philosophical. While ordinary consciousness is a series that intuits the immediacy of what it is (assuming it to be truth), philosophical consciousness follows through with this intuitive immediacy via conceptual mediation opening a differentiation (and finds out what it really is as a result). Thus, the ordinary consciousness is thinking in terms of spatial presence of identity, and philosophical consciousness is thinking in terms of a temporal becoming or even a nihilation of time (as Hegel does suggest that the “time form” is discarded in absolute knowing). This second series that Hegel opens up in the Phenomenology, is the series he is hoping to attract as a readership of the Science of Logic, that is to say, he is hoping for a readership that is able to gain a deeper understanding of the concept as such, that is no longer enslaved to an immediacy of intuition without conceptual mediation.

Here we can elaborate in greater detail on these two forms of consciousness. The ordinary consciousness is the subject of experience (the subject whom is the subject of Hegel’s science of experience). The subject of experience is attempting to represent its existence as consciousness, self-consciousness, reason, spirit and religion. But the second series, the philosophical consciousness, reflects ordinary consciousness as an empty mirror, and both sees its truth, as well as helping the other to find its own truth. What the philosophical consciousness understands about ordinary consciousness is that its representations are a search for a missing self-identity, or the lack of a home for self-identity. Philosophical consciousness in-itself is at home in the self-relating negativity, it is its own abyssal home. In other words, what ordinary consciousness thinks is the truth of its representations, is the direct immediacy of their content, but philosophical consciousness sees the underlying immediacy as the unconscious mediation of finding a home for self-identity. Yet another way of saying this is that ordinary consciousness is alienated, and doe snot know what it is, whereas philosophical consciousness is, one might say, reconciled with itself.

The ultimate philosophical consequence of this development, is that Hegel, as well as his contemporary Johann Fichte, have no more need for a unity between intuition and concept. They are thus free to think the concept in-and-for-itself (opening to the Science of Logic). The unity of intuition and concept is only necessary for ordinary consciousness (that has yet to apply the science of experience to its own path of becoming). Before applying the science of experience, ordinary consciousness attempts to dissolve conceptual distinctions, and finds the process of conceptual differentiation alienating as a simple negativity. After applying the science of experience, ordinary consciousness becomes philosophical consciousness through affirming conceptual differentiation, and negates the negativity. Here the truth becomes an unfolding conceptual process, where issues of truth in differentiating experience can be resolved via conceptual mediation aimed towards satisfying subjective interests in history.

But here, on the nature of philosophical consciousness, Hegel also starts to move beyond Fichte. For Fichte, philosophical consciousness is the pure Absolute I, in a state of absolute freedom from any tension or any limitation from the brutal natural necessity that constrains and alienates the ordinary consciousness. In this way, Fichte sets up a science of experience where the subject is oriented and organised towards this state of pure liberation from tension and limitation. For Hegel, on the other hand, the Absolute is nothing but the becoming of the substance as subject. In other words, for Hegel, the Absolute is nothing but the historical subject, as structured by tension and limitation. The historical subject is not free in the removal of limitations and removal from brutal natural necessity, the historical subject is free in working with the limitations and brutal natural necessities. In humanising nature through its labour and work efforts, the Absolute becomes what it is, not on in-itself, but in-and-for-itself. From this move, Hegel negates Fichte’s negation, by perceiving in limitation the very Absolute itself as a historical process.

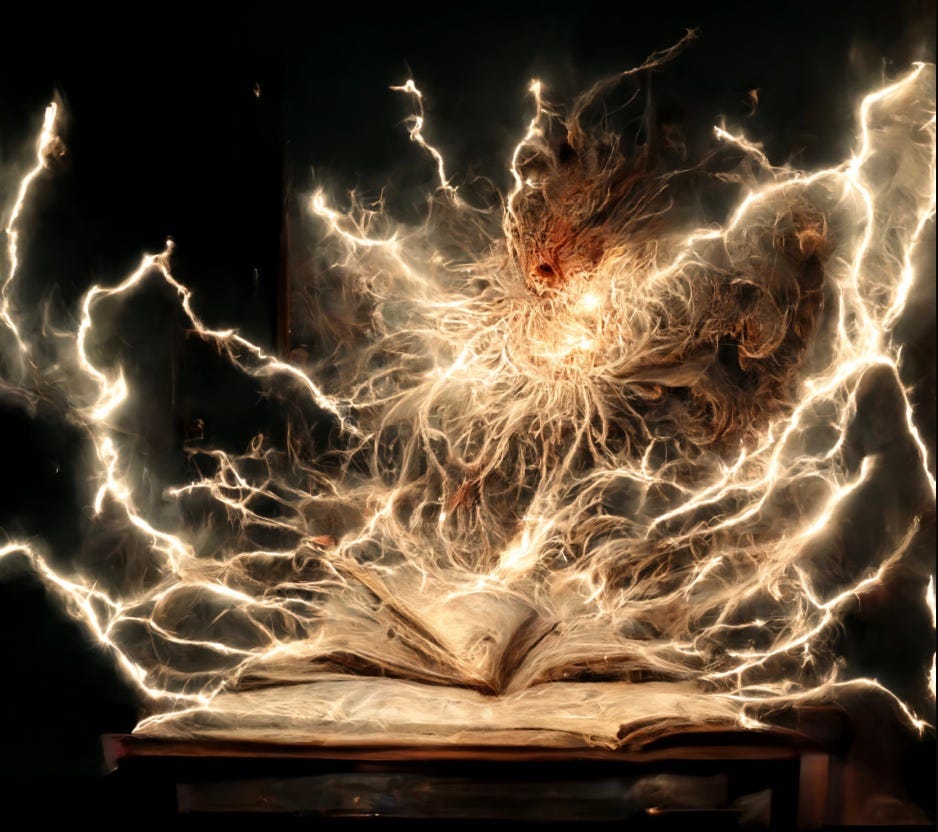

For Hegel, Fichte’s system in relation to philosophical consciousness adds what is unnecessary and impossible: a form of subjectivity that annihilates subjectivity itself in a state of Absolute Freedom. In contrast, Hegel thinks that all that need be “added” to limited historical subjectivity is a type of subtraction, as a negative state of knowing. The first series of representations, ordinary consciousness, need only conscious awareness of what it is, and this is the philosophical consciousness. The historical subject is an entity humanising objects through labour. It is the satisfaction that the subject achieves through transforming nature by spiritual labour, which marks the progress of the Absolute as a limitation transubstantiating itself, and in the process, becoming what it really is in and for itself. Conversely, if the subject were to achieve a Fichtean Absolute Freedom, there would be no possibility to transform nature by spiritual labour. In other words, in Fichte’s Absolute, even the Absolute disappears into its own extreme self-positivisation. As it regards to Hegel’s Absolute, the image that may come to mind here, and one that Hegel uses himself in the Phenomenology, is that of an embryo becoming an adult, like a seed becoming a tree. This very unfolding, where the logic of what one becomes as a result, was already there from the very beginning. Hegel simply makes this notion intelligible on the level of philosophy, he spiritually mediates the process of becoming, as opposed to it unfolding unconsciously, in the immediacy of organic form.

Now, after having covered Hegel’s differentiations from both Schelling and Fichte, we can return to the Phenomenology of Spirit itself, as the “phenomenological turn” before the Science of Logic. We can say that this entire book is an account of spirit’s increasing awareness of itself, as it becomes what it has always been, or as it actualises the potential of what was there from the beginning. As one learns through traversing the Phenomenology one becomes this by testing oneself in the real of life, and the real of life, is itself the intro to philosophy. Once spirit reaches the state of absolute knowing, through this self-testing, and becomes proper philosophical consciousness, spirit recognises that it is a self-justifying reason. In other words, there is no reason outside of it, which could be its reason or cause. While spirit stops looking for reasons and causes outside of itself, it also does not do away with reason and cause, but has a more empowered relation to both. The subject, through its work, the labour of the negative, has dissipated the contingency which obscures its nature, the accidental conditions of its world, and makes them its own, spiritualises them. In the very work of spiritualising contingent appearances, it makes them necessary, it turns the in-itself to an in-itself that is for-itself. It simply recognises itself as the creator, as inside the mind of God as the becoming of spirit.

Now looking at the Phenomenology from the vantage point of our present moment, our own mediation of immediacy, we can say that it is an account of the development of spirit in a mode known as Western culture. Hegel wanted to encourage his readership to internalise the unfolding of the spirit’s notion in the whole of Western history, before confronting the Science of Logic. However, for our time, one may also say that this account of the development of spirit requires a new interpretation on the level of global culture as a whole. This does not mean subordinating Western history to the esoteric mystical secrets of the East, but it does mean taking into account the various interconnected global-cultural forces on all continents, inclusive of Westerns fascinating with Eastern mysticisms, Eastern adoption of Western culture and values, as well as African and Amerindian developments. What is essential to engage this task, is to apply Hegel’s basic logic, which is that the logic of what spirit is in and for itself, is a paradox of being both a priori, governing the process from the beginning, and historical, unfolding as a becoming.

This paradox is at the centre of Hegelian interpretation: how can Hegel’s logic be both a priori and a historical unfolding? The move to turn the eternal into the historical, or the universal into the particular, is perhaps Hegel’s great philosophical gesture, and the most profound gesture, since Plato. Plato saw the concept as the opposite of historical particular becoming, as the real actual outside of our illusory and empty appearances. Hegel saw the concept as universal only through historical particular becoming, as the real actuality of illusory appearances as a necessary detour to the state of true knowing