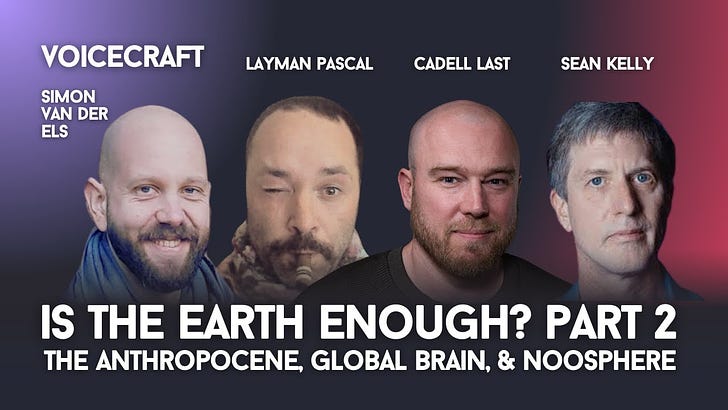

This past week the continuation of the “Is the Earth Enough?” series continued on

with , Sean Kelly, and Simon van der Els. You can find the video here:What you will find below is an expanded body of the framing for the video. The motivation behind this framing is to move the discussion from an “Earth-centric” point of view to a “Human-Earth relation” point of view. In this move, I attempt to mobilise three concepts that have emerged in only the past 100 years to think the “Human-Earth totality”, and situate them in an interconnected triad which could open new ways of thinking about the “whole”. These three concepts are:

Anthropocene as representing a hypothetical new geological epoch

Global Brain as representing our emergent technological network

Noosphere as representing the planetary sphere of thought

All of these concepts are extremely new on the timescale of human civilisation itself. The Anthropocene is a popular geological concept, and even if its formal use in geology has been rejected, I think the fact that the concept has caught on in the popular imagination signals something important which the future of formalised geological investigation will have to reckon with at some point.1 What it signals is that the human phenomenon is, on the scales of geology, extraordinarily strange, and excessive in relation to the planet thought as an independent entity. The human phenomenon is a superorganism, and more specifically a civilisational process, that has utterly transformed the planet’s surface. This transformation is so dramatic that records of our presence will read like a 10,000 year explosion from the hypothetical point of view of a geological observer millions of years in the future.

The Global Brain is a technological concept which finds its origin in the 1980s/1990s, specifically in circles focused on the emerging nature of the internet and its global consequences for human civilisation.2 My doctoral supervisor, Francis Heylighen, as well as close collaborators like Ben Goertzel and Johan Bollen, were a few of the pioneers of the concept. They suggested that the internet is structurally homologous to neuronal patterns we find in the human brain. This concept also forms the basis of my doctoral work, which attempts to situate it in relation to ideas about technological singularity.3 Philosophers like Daniel Dennett picked up the concept and developed it as a type of cognitivist metaphor: as our species developed large brains to predict and anticipate danger further into the future, allowing for long-term planning, perhaps the planet is growing a brain so as to protect the biosphere from future catastrophe.4 Indeed, modern science itself has mapped the surrounding universe to such an extent that the Earth could now be hypothetically protected from many potential future disturbances.

Finally, the Noosphere, while the most philosophical and spiritual of all the concepts, is also the oldest of the three. The concept of the Noosphere was developed in the 1920s and 1930s by thinkers like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Vladimir Vernadsky,5 and has since formed the basis for much thinking within both New Age spiritualist circles, as well as more future-oriented religious cosmologies. The basic idea of the Noosphere is that the human superorganism’s own thinking process is a new spherical layer, analogous to the geosphere and biosphere, which is in the process of forming a planetary dimension of reflective awareness. In this sense, while the Noosphere is not new, it has been historically fragmented in different civilisational constellations (e.g. Roman consciousness and awareness; Chinese consciousness and awareness, etc.), but now we are entering a mode of a truly species-level consciousness and awareness. While New Age thought orients or orbits the unification of global species-level consciousness in the unification of “East-West”, it is possible that this thought needs to be significantly modified with the complexities introduced in the concept of the “Global South”.

How can we think these concepts philosophically, universally, as well as in their triadic interrelations? The Anthropocene brings us to the question of our ecological and geological stability or sustainability in the sense: “can our species balance long-term with the Earth?” Is our species-being drive so excessive in relation to the planet we find ourselves inhabiting that we threaten its balance in the same way that an asteroid impact threatens its balance? In the process, does our drive undermine our own conditions of possibility of being a species-being? These questions invert the standard modes of thinking about humans vis-a-vis natural being in the sense that, classically, we have always conceived of humans as impotent vis-a-vis the mysterious impenetrable forces of nature. But what if actually, the Anthropocene signals the moment where, our collective force as a species-being is actually more monstrous, or becoming more monstrous, than the natural forces that gave birth to us? In short, what if the forces of science and technology are inverting the power relation between human beings and the planet? But this inversion should not be thought in the rationalistic enlightenment or romantic sense, where human beings control nature towards our own desires, but rather where human beings are forced to confront their own irrational self-destructive drive? In such a context, the Anthropocene challenges us to a responsibility for the collective unconscious of the species-drive itself.

Here the Global Brain can be a useful concept in the sense that it is designed to stimulate thinking about socio-technological coordination on a planetary level. In the same way that our individual brains biologically or neurologically coordinate “globally” to produce our individual sense of consciousness, the technological infrastructure of the internet is itself a medium that — while challenging the pre-internet structures of our institutions and nation-states to reinvent themselves — also presents to us the opportunity for new global coordination. Here we find not the external geological limits of nature as the problem, but rather the problem of our own species-being’s aggressive drive as the problem. Historically humans have been limited to local coordinations (from tribes to nation-states), and in these conditions our species-being has always and constitutively been riddled by tribal conflict that often leads to excessively violent situations and conditions. However, as we learned in the 20th century, if this pattern of activity repeats on a global level (e.g. WW3), we risk further undermining our species-being foundations. Here we find a “double-negative” (external nature and internal drive) that could force the challenge of real global coordination, or not. Philosopher Slavoj Žižek has suggested that this points towards the idea that “communism” will appear, not as a positivist utopian cause, but rather as a response to a global catastrophe or negativity.6

Whether this double negative forces global coordination is not deterministic but arguably depends on the indeterministic nature of our “Noosphere”, that is our planetary consciousness and awareness. While the abstract universality of this reflection has been in our popular awareness for the last century, the hard philosophical, scientific and theopolitical work of this challenge is still very much before us. When it comes to fully confronting both our external and internal excessive drive for self-destruction it is hard to stay with Aristotle’s classic definition of our species being as a “rational animal”, but probably challenges us towards the Lacanian idea that we are the “enjoying animal”. Crucially, this “enjoyment” is not reducible to pleasurable satisfaction and the reduction of tension, but rather the “joy” we can get from excessive tension itself, an excess that threatens our being itself. While this may sound extreme, any sober analysis of the nature of our species being in history forces us to consider its possibility as the real. The question that naturally arises from such reflection is something like: how do individual humans reconcile with the body in terms of collective libidinal enjoyment and the power differentials it produces beyond repressive mechanisms (either neurotic or perverse)? This question has implications for both the excessive drive of the species being (for expansion, extension), as well as for the inherent internal conflict and war of our species-being (our tendency to violent tribal schism and self-destructive spirals).

In this context, and when thought together, triad of the Anthropocene-Global Brain-Noosphere, brings us to a “theological-speculative split” between traditionalist reifications and absolute negativity. Can we truly think a “Religion of the Planet”? Or alternatively, will a “Religion of the Planet” emerge? Such an emergence may circulate around the question of how long we can prolong the reproduction of the human species: are we aiming for a planetary civilisation that can last millions of years? To think about our entire species as an interconnected entity on such time scales boggles the mind, and the hard work implied by the concept has barely been approached. From a properly philosophical speculative mode: maybe it is the wrong question? But if it is the right question: how are we to deal with the balance between the nature of civilisation and the limits of ecology? What are the limits of ecology in the context of the full technological potential of our species in this universe? Are there some hard limits or will future innovations totally rewrite the possibilities of ecological limits?

Then there is the political dimension, which currently orbits the speculative dimension of the nation-state and its relation to international coordination mechanisms. Are we aiming for a planetary civilisation that has universally and sustainably raised the floor of our species-needs? If so, how are we to design planetary structures that accommodate the interconnectedness of all its members? Are nation-states still the pinnacle of our structural possibilities for explicit and public self-organisation or are we capable of more transparent and inclusive international modes of coordination? In other words, are we in a situation where international coordination already exists but simply in a non-democratic and reductive capitalist form? If we were to move towards a different structure, what forms would it take and how would it concretise? Can it really emerge through rational discourse or will it require war (absolute negativity) to actualise in response to the global catastrophe? More importantly, if it requires a negative forcing function, will the absolute negativity be so totalising that it prevents the possibility of constructively and positive responding?

Finally, the philosophical dimension, I think, brings us to the level of thought and libido (life drive): can thought reconcile with the excesses of libido? Or is libidinal thought the truth of thought? Is there more intelligence in the spontaneous enjoyment of our thinking than in its long-drawn out mediation? Moreover, in the structural automation of our intelligence, are we not more and more forced to confront the enjoyment of the body itself? Or not? This tension runs throughout the history and to the core of philosophy. This tension also runs throughout the history and to the core of psychoanalysis. In this sense, it should be little surprise that the strange relation today between the history of philosophy and psychoanalysis proves so powerful for thinking our moment. If this analysis adds anything, it is the challenge of also thinking these tensions in the interconnections between the Anthropocene, Global Brain, and the Noosphere.

The next Philosophy Portal course titled “Deleuze and Analysis” will be taught by Prof. Terence Blake and focuses on the tension between Deleuzian philosophy and the Freudo-Lacanian tradition of psychoanalysis. To learn more, or to get involved, see: Deleuze and Analysis.

Steffen, W, et al. 2011. The Anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 369.1938: p. 842-867.

Heylighen, F. 2011. Conceptions of a Global Brain: an historical review. Evolution: Cosmic, biological, and social. p. 274-289.

Last, C. 2020. Global Brain Singularity: Universal History, Future Evolution and Humanity’s Dialectical Horizon. Springer. (link)

Dennett, D. 2001. We Earth Neurons. https://kurzweilai-brain.gothdyke.mom/articles/art0293.html (accessed: December 8 2024).

Vidal, C. 2024. What is the noosphere? Planetary superorganism, major evolutionary transition and emergence. Systems Research and Behavioral Science.

Žižek, S. 2024. Christian Atheism: How to be a Real Materialist. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 232.

Cadell's framing helps so much put into concepts of what is taking place today. anthropocene/ global brain/ noosphere.

It just seems to me we can't think all three. but ability to see how they are all woven together and pointing out these irreducible gaps that turned into topological structures through analysis showing their intolockings is the opening we are needing. Taking the implicit and bringing it to explicit is the work of the spirit, revealing our unconscious. Is this our work for our time to think again, as Zizek says?

I was listening back to Terence's conversation with you and the point he makes that through hegel's owl of Minerva takes flight is the opening to a new position that was once the way was seemingly closed off.

One commoner wrote on the video, thinking that this was too abstract and not enough concrete proposals for affecting the chain of money and power. This is the difficult work of what you are doing. At first glance, it seems yes abstract lacking any concrete proposals, but it is here in these difficult positions of bringing to light these irreducible gaps that the money-power hide in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties, but tease out reduce their stink.