Labour Vs. Reform, Stevenson vs. Benjamin

Analysing the symptom of UK politics for insight into the political challenge ahead of us

“Britain is for the British” - Carl Benjamin, Sargon of Akkad

“Tax wealth, not work” - Gary Stevenson, Gary’s Economics

The Early Marx 101 course at Philosophy Portal is unfolding throughout 2025.1 To start our course, we have made a lot of space for Marx’s Critique of the Philosophy of Right, his response to Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, which was first published in 1844.2 Marx’s early text is attempting to address, not only what Marx believes to be Hegel’s mistake in an analysis of the political real,3 but also attempting to address the radical separation that appears internal to European politics after the French Revolution. This separation involves the emergence of the modern nation state, where we find a gap between the individual’s real life in society (under the logic of capitalist industrial production), and the political life of the citizen of a state (what we could call the dominance of bourgeois society). This ultimately leads to the “second French Revolution” (of 1848) where we find a fundamental conflict between liberal democracy (and its bourgeois values) and industrial capitalism (and its logic of capital), which has not only been left unresolved, but which we now find exploding in the context of new waves of industrial production (e.g. artificial intelligence) which threatens to deeply disenfranchise the middle class and the next generation, without a new politics to deal with the situation.4

In this article, we want to keep our attention on this gap between the individual’s real life in society (under the logic of capitalist industrial production), and the political life of the citizen of a state (what we could call the dominance of bourgeois society), because this gap is politically radioactive throughout the Western world and the many turns to populist political organising (on both the left and right). We will focus specifically on the political situation in the United Kingdom, through the lens of the Labour Party led by Prime Minister Kier Starmer and the Reform Party led by British politician Nigel Farage; but also the new up start party Restore Britain which is not only further to the right of Farage’s Reform, but also a sign that Britain elite is beginning to fraction internal to itself.5

However, to start, I want to say that this analysis on Labour vs. Reform, is simply a case example that represents an opportunity to learn about general political movements throughout North America and Europe (especially as it relates to the emergence of right wing populist defection from mainline capitalist politics, starting with Donald Trump in the United States of America). I think that in these general political movements we find a right-wing populist surge which is organising itself around immigration and nativism, on the one hand; but also, and what we will build up towards, a left-wing populist surge which is organising itself around inequality and taxation, on the other hand. How are we to think this tension or symptom in our political landscape, and what political lessons can we learn from the “Early Marx” in regards to it? Is Marx still our contemporary?

To set the stage for the broader general political phenomenon throughout North America and Europe, consider the following quote from Jordan B. Peterson who recently platformed German politician Christine Anderson for a discussion centred around the rise of right wing populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD) around issues of immigration:6

“You got a radically centralised Europe where the distance between the citizens and government grew to slave-tyranny proportions. […] The real seat of power and decision-making authority reside in organisations like the WEF [World Economic Forum] and EU [European Union]. […] The AfD has been described by the progressive mob as “far-right”. [But] I am quite curious about the AfD, the rise of populist right wing, classical conservative parties throughout Europe, like with Reform in the UK. I am curious about this phenomenon. It is time to discuss immigration, unrestricted immigration into Europe, into Germany, the Euro, the European Union, globalisation, net-zero, and the Covid-tyranny. [… insert story about Pakistani Muslim Rape Gangs in UK]”

In this quote we want to pay attention to the aforementioned gap between the individual’s real life in society and the political life of the citizenry of the state, where Peterson is interpreting this landscape as a gap between slaves (individual’s real life) and tyranny (political life), specifically in the context of the European people and the European Union. What is characteristic of the populist right is the belief that the European Union is an international organisation that is preventing European nations from being able to defend their borders from waves of immigration (both within, but especially outside, of Europe), and consequently, being able to defend and build up their own national culture, language, and ethnic identity.

I throw in the reference to “Pakistani Muslim Rape Gangs in the UK” in the above cited quote because this phenomenon is the main “political football” that the populist right uses (in the UK, but other similar examples in other national contexts).7 Here I am not bringing focus to the obvious brutality of the situation (e.g. “grooming gangs”), nor the political mistakes (“fumblings”) of the Labour Party or other parties in handling immigration in general; but rather bringing attention to the way this “football” is used in order to create the image that immigration is leading to a zero-sum culture war between “black and brown men who are a threat to our white women”, on the one hand, and the “white working class” just trying to live an honest life, and having their country stolen by “Asiatic and African-Muslim gangs”, on the other hand. In the extreme, the populist right narrates a situation where the spectre of endless immigration leads to a replacement of the white working class by black and brown bodies, but also Islamic ideology, and in the process, the loss of any notion of “British-ness” or “European-ness” as the cornerstone of Western civilisation.8

The difficult thing for liberals, and I would also add Marxists, is actually understanding how this discontent, coming from the white working class, is to be recognised in its legitimacy, while at the same time rising above the right wing populist temptations (scapegoating Muslims or other immigrant populations).

In order to dive deeper into the general phenomenon, I am going to use two specific political examples from the UK: Carl Benjamin of Sargon of Akkad,9 and Gary Stevenson of Gary’s Economics,10 to demonstrate both the sentiments leading to the emergence of a populist far-right, as well as the most prominent current response to it on the populist far-left.11 Benjamin can be associated with the populist right, not only Reform but also Restore, and again, organising around the issues of immigration and nativism; and Stevenson can be associated with a populist left, who attempts to appeal to all positions of the political spectrum, but is probably most associated with the Labour Party, and an internationalist left concerned with the problem of wealth inequality and taxation.

In this I would like to ask a central question: who speaks for the working class?

In light of this question, I think we should also consider the way in which the working class throughout the Western world is being torn apart, even to the level of approaching the problem of a civil war, or various interconnected civil wars. Professor of war in the modern world, David Betz, suggests that we are now entering the causal situation for a civil war in the United Kingdom, and perhaps throughout the Western world.12 He notes three reasons contributing to this “causal situation”:13

Polar Factionalism: people are no longer strongly disagreeing about polarising issues (e.g. feminism, death penalty), but differ on the basis of what they perceive to be the consensus view of their tribe (e.g. we need to re-introduce the death penalty, or we need to abolish more-recent liberalising waves of feminism).

Downgrading (or also: replacement narrative): formally dominant majority either losing its status or fearing that it is losing its status in its own homeland, leading to the formation of new counter-cultural mass movements incentivised to action.

Loss of Faith (in political legitimacy): people losing faith in the capacity for politics to function on solutions of collective action problems, expressing a lack of systemic legitimacy (often measures by trust, which has been measured for decades now, and which most Western societies are at all-time lows).

In using the examples of Benjamin and Stevenson, this article is seeking to analyse in microcosm all three of these issues:

Benjamin and Stevenson do not just strongly disagree, but their disagreements lead them outside of conventional two-party political solutions (towards national and international socialism, respectively).

Benjamin and Stevenson are both responding to the perception of downgrading, where Benjamin explicitly points towards replacement narrative discourse, and Stevenson points towards this being used to obfuscate the true cause of decline

Benjamin and Stevenson are both extremely distrustful of contemporary two-party politics (Benjamin re: Reform, Stevenson re: Labour); with Benjamin looking to Restore Britain and Stevenson looking for a reformed Labour

If we are going to simplify both Benjamin and Stephenson’s positions, and perceive these figures as general representatives of populist right and left-wing politics today, we can say something like:

Benjamin wants “Britain for the British” (which he extends as a general internationalist principle: “Pakistan is for Pakistani’s” “India is for Indians”, “Nigeria is for Nigerians”, and also: “Israel is for Israelis”);14 and

Stevenson wants us to “Tax Wealth, Not Work!” (which he emphasises must be pursued as both a national taxation policy, but also extended to an internationalist coalition willing to redistribute wealth in excess of 10 million pounds)15

For the right wing populists, we thus find the seeds for a politics of “hyper-ethnic nationalism”, extended universally. The crucial moment for this politics is a “defusing” or a “break down” of the “World War 2 consensus” that “Hitler” and the “Nazi Party” represent the ultimate “Satanic Evil” in our civilisation, and actually had a point about what we might consider “national socialism”.16 In this defusing and break down, what opens the discourse, for them, involves not only the capacity to talk about “far-right” issues and concerns, but also to forward a party politics (e.g. Restore Britain) which is based on these “far-right” concerns. Here the position of Israel, as a nation-state that is more or less explicitly based on an ethnic-religious foundational fusion, is perceived as not only correct, but a model which should be universalised to other ethnicities and religions (e.g. Israel is founded on an ethnic-religious foundation-fusion, and thus so should Britain, or insert X country).

In this context, while Benjamin does not seem to support a Christian nationalism — as he represents more of a “secular populist-right” — what we find if we look closely, is the seeds for a kind of “Christian ethno-nationalism”. Here we may find figures like Jordan B. Peterson actively supporting such a direction, with his closest religious association, Jonathan Pageau, struggling with the in-between space of an explicit Christian nationalism to support far-right politics,17 and a more Christian “wild spirit”, which does not connect its religiosity to an explicit nationalist political agenda, most notable in figures like Paul Kingsnorth, a former ecological activist, and recent convert to Orthodox Christianity.18

For the far-left wing populists, we find a program of a broad reform of capital, which must take place on both the level of the nation-state and the international level.19 Of course, the far-left wing populist reform of capital will argue that the far-right populist reform is misguided in its understanding of immigration, and its belief that immigration is the cause of a general societal and economic breakdown of the nation state. For the far-left wing populist reform there is the idea that the general societal and economic breakdown of the nation state is something not unique to Britain (or Germany, or the United States of America), but rather something that is shared broadly by all developed countries today, and thus demands an international coordination in order to resolve. Of course, once we go as far as possible in this direction, the far-right populist reform will see the seeds of Marxist communism and the threat of 20th century communist terror, collectivisation, command economies, gulags, and the like. Consequently, for the far-right populist reform, the very idea that our current societal and economic breakdown requires a response that goes above the nation state, is itself a part of the problem (hence the tendency to scapegoat the European Union and other international organisations).

In this context, I would argue, the real conversation can never actually start, and instead what we see as a political symptom, are the reconstruction of these far-right and far-left poles, which cannot speak to each other. Again, this is a recipe for what David Betz would call civil war, on the basis that the belligerents were under the same sovereign authority at the beginning of the conflict, but find themselves occupying positions that call for totally other systems of authority and legitimacy.20 Thus, in order for us to consider our situation a literal civil war, we would have to find ourselves in a situation of an internal splitting beyond the established system, and we would have to find ourselves in a situation where this splitting is not just an revolutionary upsurge and explosive event, but rather a prolonged process that gradually tears apart the social fabric of the nation.21

Since I mentioned the theological dimension of the populist far-right,22 I will add that the theological dimension is something seemingly foreclosed among the populist far-left. This foreclosure leads to strange symptoms that are difficult to disentangle when it comes to the relationships between Christianity and Christian nationalists, Israel, Judaism and ethno-religious nationalism, and Muslim, Islam and the spectre of Islamic theocracy (Sharia law as a replacement for modern constitutional law).23 In general, what we find among people who both live in Western Europe or North America and consider themselves leftist is a general negation of Christianity, and a general celebration or acceptance of Islam as part of the emancipatory core of contemporary politics.24

While this dimension is not active in Gary Stevenson’s work, who himself does not seem to embody either of these theological tendencies, it is worth noting the theological background that we can see in the contemporary political landscape, as I do not think it is irrelevant to the future of the conversation. For insight into the way this theological background may become relevant — even to Stevenson as an economist, who does not often brand himself as an expert relevant to any other field — consider the reflection of economist Ha-Joon Chang, who recently spoke with Stevenson, and whom Stevenson referred to explicitly as his “favourite economist”:25

“Economics has become like Catholic theology in medieval Europe, it has become the language of the rulers, so if you don’t speak economics you cannot participate in any debate.”

What I think is especially important to highlight in the perspective of Stevenson’s favourite economist, is the way in which we need to take seriously that we cannot even find the proper starting point for the conversation, because in order to find the proper starting point for the conversation, there would have to be a “Protestant Reformation of economics”. Stevenson often points to how the professional field of economics not only requires more class representation (i.e. the field is often populated by the wealthy), but also that the actual economic models that are used to make predictions, fundamentally factor out the dimension of inequality.26 Does Stevenson represent one of the seeds of that “Protestant Reformation of economics” (i.e. more class representation in the field of economics focused on building models that factor in inequality)? Or will the debate be fundamentally entangled to the populist right scapegoating of immigrants and internationalist organisations leading to an explosive civil war?

For now, let us return our gaze to Benjamin, and give him a fair hearing on the issues that disturb him the most: immigration and nativism. Here let us return to the notion, inspired by Marx’s Critique of the Philosophy of Right, that what we find at the birth of the European nation state is a radical separation of the individual’s real life in society (e.g. white working class), and the political life of the citizen of a state (e.g. Labour politicians, or EU bureaucrats). We can actually mobilise this Marxist perspective to help frame Benjamin’s main concern: the modern bourgeois liberal nation state does not serve the actual real working class people who natively inhabit the land.27

In a video focused on Muslim immigration titled “How Bad are Things Going to Get?”, Benjamin states:28

“I am not sure if conservatism is what we need [what is there to conserve?], we need some form of nativism, frankly. Because the question that really underpins all of this is, is to whom does England belong? And we know that Palestine belongs to the Palestinians, who know India belongs to the Indians, and the question of to whom England belongs is left hanging in the air.”

This quote should make clear many of the threads articulated above about what fundamentally motivates right-wing populism and the model that they support as a strategy for what they perceive to be an internationalist chaos leading to the loss of shared ethnic identity, cultural and linguistic homogeneity, and secular religious tolerance. In the current political landscape, for Benjamin, Britain does not have a future because there is nothing “British” about what is happening to the demographic core of the country.29 Throughout the video, he uses UK “Census maps”30 to analyse the ethnic distribution of different regions of the country, highlighting that there are many urban regions which are now so dominated by immigration that under 1% of the population is “ethnically British” (classified as “White English, Welsh, Scottish or Northern Irish”).31 While highlighting these regions, Benjamin will refer to them explicitly as “infestations” that needs to be purged or cleansed from the nation, which is arguably how you get the early seeds of fascist, or at least “national socialist” organisation.

This rhetoric is leading to a situation where the biggest party in the UK, and arguably the party that will win the next general election, is Nigel Farage’s Reform.32 The support for Farage’s Reform grew substantially last month after the Glastonbury music festival, where a hip hop act in connection to the Northern Irish group Kneecap, Bob Vylan, performed on a stage with a banner behind him stating “This country was built on the backs of immigrants”, while rapping a song with the hook:33

“I heard you want your country back? Shut the fuck up!”

Benjamin immediately released a video titled “They’re Doing Us a Favour”, arguing that this type of performativity is going to drive more and more reasonable working class people to the populist right. From Benjamin regarding Bob Vylan:34

“Here we have a half-Black man saying “shut up, stop complaining, you are going to be a second class citizen in your own country, and that is the way things are going to be, because all of the power structures around me agrees you should be disposed of your native land.””

In this same video, Benjamin quotes a tweet from Farage, directly responding to Vylan’s performance, which states:35

“If you vote Reform you can have your country back from these lunatics.”

One of the most interesting things about Benjamin’s general commentary on the Glastonbury Festival, included his observations about its demographics: mostly middle-aged white middle class individuals who live in mostly white-dominated neighbourhoods; as well as the hypocrisy about calling for an end to “wall building” and the beginning of “bridge building” when the festival itself was surrounded by a giant wall keeping people out who could not afford to attend the £400 event.36

What is perhaps most interesting about Benjamin’s assessment of the situation, especially as it relates to the demographics of the Glastonbury Festival, is how it reflects Marx’s own position on the threat of governmental bureaucracy in the Critique of the Philosophy of Right:37

“Those who are entrusted with affairs of state find in its universal power the protection they need against another subjective phenomenon, namely the personal passions of the governed, whose primitive interests, etc., suffer injury as the universal interest of the state is made to prevail against them.”

In the case of Benjamin’s critique, we have a middle aged white middle-class bureaucrats, who use the universal power of the state to defend themselves against the personal passions of the governed and their primitive interests (i.e. in this case, the white working class of the UK who are attempting to defend their ethnic heritage). However, while we can find agreement between Benjamin and Marx on this issue, in the same way that we find national socialism downstream of failed Marxism in the 20th century, we may find the same pattern in the 21st century.

Consider that, at the moment, this situation looks like a clear win for Farage and the Reform Party. And if we look downstream of it, we find the party that Benjamin actually supports: Restore Britain, a new party led by British politician Rupert Lowe.38 For Restore we find the following program:39

Purging of institutions funded by the state

Banning of the Burqa/Niqab

Deportation of illegal migrants

Net negative immigration

Defunding of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), and

Restoration of the death penalty

In a recently released framing of the Restore Britain Party platform we find the following rhetoric from Lowe:40

“Albert Einstein said presciently, “the world will not be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch them, without doing anything”. The post-war European elite had a plan to destroy the nation-state, which they saw as the root-cause of war, particularly between France and Germany, in order to create a Europe-wide, elite socialist protectionist bureaucracy. The United Kingdom was the proudest sovereign nation, founded on the Glorious Revolution, the Bill of Rights in the 1707 Act of Union, and had not been invaded, occupied or oppressed like most of Europe. The post-war plan, which our elites supported, involved undermining our sovereignty, through deceit, in order to overtly work towards a borderless European Union, presided over by an unelected commission[.] In order to subjugate our proud nation, we were divided into regions, and old rivalries rekindled through creation of senate and the Scottish parliament. Proud England was sacrificed, and we were sold out by a leadership that preferred to surrender our sovereignty, to a continental construct, based on a Napoleonic legacy. Parliament, the civil service, and our constitutional structures were gradually, and then swiftly undermined under Tony Blair, only avoiding the fate of the Euro thanks to James Goldsmith Referendum Party. [insert grooming gangs story, Pakistani Muslim-men raping White women; doctrines of failed liberal multiculturalism/open-border EU; collapse of main-line two-party system (Tories and Labour)] We now need a committed movement of common sense to Restore Britain. I don’t know about you, but I want my country back.”

What we see in the above rallying cry from Lowe is again a scapegoating of the European Union as a socialist project, the belief that this has led to the undermining of Britain’s national sovereignty, and the emergence of an open-border liberal politics which threatens the common people of British heritage. Will some combination of Farage’s Reform or Lowe’s Restore lead to the world that the working class people of Britain want? Or does it further obfuscate and blind us to the political challenges before us?

In order to find out, we should think about how these problems are framed by Stevenson and the left-wing populist response. First off, Stevenson’s work emerges from his studies and his career in economics, and he does not propose to be pro or anti-immigration, while at the same time recognising that the populist right parties will respond to his work through the spectre of that lens. What is interesting and challenging about framing Stevenson as in a type of strange dialectical unity with Benjamin in the context of looming civil war, is that it represents the way both right and left wings of normative party politics are fracturing and new frames and approaches are forcing their way to the surface in both orientations.

To understand Stevenson’s position we should first understand his history and why his history is actually the key to his current success as a voice for an internationalist left. Stevenson originally started his career as an economist and day trader betting on interest rates.41 During the financial crisis of 2008, interest rates went to zero, and his job was to bet on when interest rates would go back up as a proxy for the recovery of the economy.42 Stevenson claims that everyone in his profession thought that interest rates would rise again very quickly, but they did not. In this context, he attempted to understand why the economy was not recovering, and started to hypothesise that the problem was intimately entangled with economic inequality: ordinary families were being “squeezed out”. From this hypothesis, he started to make “pessimistic bets” on the non-recovery of the economy, and became one of the most successful leaders in the world on that basis.43 Since this time, he gained financial independence, and started to figure out ways to stop the rapid growth in inequality and living standards. For context, in relation to the aforementioned Professor of war in the modern world, David Betz, he, like Stevenson, believes that if this problem is not fixed, we are looking at a repeat of the 2008 financial crisis.44

Consequently, Stevenson points towards the need for a reform of economics on the issue the inequality, and proposes concrete policies that can start to fix the problem at the root cause of the issue. However, at the same time, Stevenson is aware that the right wing populist movement, and the issue of immigration, can be used to distract the working class from organising towards these ends:45

“The power is not really with the people, its with the two party system. […] But if the conservative party gets smashed it might get taken over by reform […] as more anti-immigration. […] Reform uses immigration as a wedge issue [dividing pro-immigrant left parties from ordinary people who think immigration is too high pushing wages down and house prices up].

Stevenson continues:46

I think the primary reason why life is getting harder is because of inequality, not immigration. […] But I don’t know how to stop ordinary people […] from thinking that the reason why they can’t get a good job and a house is because of immigration.”

From this quote, we should once again concentrate on the aforementioned Marxist distinction pointing towards the radical separation of the individual’s real life in society (e.g. white working class), and the political life of the citizen of a state (e.g. Labour politicians, or EU bureaucrats). Whereas Benjamin can in a way exploit the “common sense” perception that immigration is the problem, Stevenson has to tarry with the higher order dialectic regarding the very separation/gap at the heart of modern politics itself. On the one hand, he is aware that a large part of the working class will perceive immigration as the problem, and right wing populist parties can weaponise that common sense for their political purposes. On the other hand, he is aware that immigration is not really the cause of the problem, but a wedge issue, that can obfuscate and blind us from the challenge of inequality, which requires a higher order unity to confront. This is something where we again find agreement with Betz, who suggests that there are three major bulwarks against civil war, with the primary bulwark being wealth:47

Wealth: if there is a lot of money in the social system, then even if their are cracks and tensions, money can lubricate or paper over those conflicts. But the UK (and the West as a whole) is coming to the end of its capacity to finance debt (paper over the cracks).

Culture or Habit of Obedience: after a number of generations of good governance, people are acculturated to do the right thing, even in the face of elite corruption, but we are now in a situation where that culture/those habits are breaking down.

Emergence of Expectation Gaps: when there is large difference between what people expect to receive (primarily material, but also prestige) and what they actually receive, we enter a danger situation. In our situation, we are producing an enormous expectation gap between generations which is likely to grow larger due to the automation of white collar labour.

For all of these factors, taken together, Stevenson’s work is emphasising all three:

We cannot keep the same system that has been in place since the 2008 financial crisis, papering over cracks with money (debt financing)

We need a new mobilisation of the working class that breaks from the governing elites who can no longer be trusted to make decisions based on growing inequality, and

Generationally we can no longer expect to live better lives than previous generations, with proxies home ownership and rate of savings at equivalent age, as well a everything that flows from that, decreasing from the Boomer generation to Gen X to Millennial to Zoomers.

At the same time, Stevenson is painfully aware that the populist right and the issue of immigration specifically, could undermine the entire effort to approach inequality:48

“I am very confident the economic situation will get worse because the inequality will get worse. […] The left is going to have to consider the moral need to protect immigrants which will divide them more from ordinary people and the left will die; the right will come in and reduce immigration but it won’t fix the living standards problem.”

Stevenson continues with reference to 20th century history:49

That starts to remind me of what happened in the early 20th century. […] I have been trying to build a political coalition on the left around inequality but I’ve been failing. […] I want to tax rich people, the rich are getting richer and richer and richer. Ordinary living standards are collapsing. The rich don’t want that. […] The rich will offer to kick out the immigrants. […] It has happened again and again throughout history: inequality rises, living standards fall, and the easiest thing to do is sell you a scapegoat to divide the working class.”

Here, of course, Stevenson is referencing the history of the 20th century and the emergence of national socialism in the 1930s and 1940s. This should be connected to what I referenced earlier in reflecting on Benjamin’s position, where there is a definitive “breakdown” of the “World War 2 consensus”, which is opening up considerations along the lines of “maybe the Nazi Party/national socialists” had a point. The sentiment is usually not so far as to turn Hitler from a figure of Satan into a figure of true emancipation (for white people), but it does lead to a sentiment that we need a national socialist politics to protect and reify national ethnicities multi-locally in response to the perception of a complete open-border immigration policy, with distinct asymmetries stemming from Arabic and African nations into European nations (what we can clearly see as the basis for the Restore Britain party platform).50

More recently, Stevenson has started to narrate a very clear picture of the political landscape as he sees it, as well as how he is positioning himself and his fight for a coalition around inequality. For Stevenson, he is clearly aware of the “far right” surges, and increasingly searches for support from “defectors” from the Labour Party who are ready to take the economic situation and class representation more seriously. He states:51

“There is kind of two flavours of government at the moment: either this boring centrist ‘let’s just be more efficient, practical, sensible, and somehow that will fix things’, and you have this kind of increasingly mentalist far right that is going crazy, but aggressively blaming immigrants and foreigners. These two types of government are typified, at the moment, by the Kier Starmer labour government in the UK, and the Donald Trump Republican Party in the USA. […] They will both fail on the economy, because both of them are failing to recognise the key fundamental problem you have: wealth inequality is growing very quickly, the rich and the super-rich are growing their wealth very aggressively, that is squeezing out bankrupting governments, and then squeezing out and bankrupting the middle class.”

Stevenson starts to depict a situation which seems like we are inescapably heading into “Marxist conditions”, that is conditions where the rift between the “bourgeoise” (capitalist elite) and the “proletariat” (working class) are pitted into a zero sum conflict leading to civil war:52

“Because wealth taxes and taxing the super-rich is not on the table, you end up with this situation where governments have collapsed their wealth, are hugely in debt, turning to a middle class, which is also aggressively losing its wealth, saying you need to pay more, and absolutely refusing to look at this group of people squeezing everyone else out, and it snot going to work, basically. […] The boat has a hole in the bottom, and you’re not going to fix it by rowing faster [e.g. current Labour Party approach], or blaming immigrants [e.g. Reform and Restore].”

Moreover, and what makes this situation even more towards a Marxist international problem, is that Stevenson is not of the belief that UK can do this alone, but rather that it will eventually require a coordinated effort between nations:53

“We are not the center of the world anymore. This is going to be very difficult to fix just here, just in the UK. It is going to be much easier if we have other countries willing to protect ourselves from billionaires. […] Please try and build up this message: the reason for falling living standards is because of inequality, governments and the middle class are being squeezed out, that inequality is continuing to grow rapidly, if you don’t do anything about it, then living standards and the economy will continue to collapse. You need to understand that, in your country as well as in my country. If we build this message up, we can stop it. The last time we significantly reduced inequality it wasn’t just done in the UK, it was done across Europe, including the US and Japan, we did it together. We can do it again.”

This seems a most hopeful message, and one that is certainly shared by similar movements in the United States of America, most notably led by Bernie Sanders, both in his previous attempts for the American Presidency, and in his current struggles in the Fighting Oligarchy Tour.54 However, what it leaves out, is perhaps the “impossible” dimension of the demand (e.g. how is an international coalition going to form in a way to regulate flows of “capital mobility” for “the people”), but also the way in which, historically speaking, the reduction of inequality has only previously been possible in the aftermath of war conditions (e.g. World War 2).

First, the dimension of building an international coalition to implement something like a “Wealth Tax” represents the central proposal of economist Thomas Piketty’s policy proposal and suggestion towards the end of his magnum opus, Capital in the Twenty-First Century:55

“To regulate the globalised patrimonial capitalism of the twenty-first century, rethinking the twentieth century fiscal and social model and adapting it today’s world will not be enough. To be sure, appropriate updating of the last century’s social-democratic and fiscal-liberal program is essential, which focused on two fundamental institutions that were invented in the twentieth century and must continue to play a central role in the future: the social state and the progressive income tax. But if democracy is to regain control over the globalised financial capitalism of this century, it must also invent new tools, adapted to today’s challenges. The ideal tool would be a progressive global tax on capital, coupled with a very high level of international financial transparency. Such a tax would provide a way to avoid an endless inegalitarian spiral and to control the worrisome dynamics of global capital concentration. Whatever tools and regulations are actually decided on need to be measured against this ideal.”

Here we should also remember philosopher Slavoj Žižek’s insistence that the 21st century is characterised by the “divorce” between capitalism and democracy,56 in that Piketty’s solution, as well as Stevenson’s political project, are aimed at the idea of a reconciliation between the two, or we might suggest, a “second marriage”. I do not emphasise this to sow seeds of doubt into the ideals of Piketty, or the political project of Stevenson, but merely want to point out that, to remain realistic, we should keep in mind the mountainous level of the challenge before us. For the “most doomer” perspective on the topic, we should here turn to political scientist Benjamin Studebaker, whose work The Chronic Crisis of American Democracy, points towards the nature of capital mobility as an intractable issue:57

“The mobility of capital continues to increase, automation and technological development continue to weaken labor’s negotiating position, and the gap between the oligarchs and the rest of us continues to grow larger and larger. How can we get used to a world that is becoming more vicious and more disappointing at such an alarming pace? Every new crisis sees a handful of billionaires grab ever more wealth from the rest of us. Workers, fallen professionals, and small employers all feel stuck in a system that doesn’t seem to care about them or about how hard they work. They know it wasn’t always this way, and they feel enormous resentment. This resentment is too powerful to be ignored. Too many people can win too many votes by feeding it. Too many people can make too much money by pandering over it. Over and over, politicians promise “hope and change” or that the “forgotten” masses will not be forgotten anymore. Over and over, media outlets point the finger at different groups in our society, turning resentment into blame and hatred. They promise us miracle cures, offering us easy solutions to complex problems. Every time they promise to help, every time they tell us some group is the only thing standing in our way, they raise our hopes and expectations. The people who tell us the problem cannot be solved, that there’s nothing to be done but play by the oligarch’s rules — these people are quitters, and they don’t win elections or get clicks. They aren’t competitive, and they’re slowly going extinct.”

And also an issue in which a wealth tax seems impossible:58

“All the work that had been done to reduce the wealth and power of the oligarchs during the postwar era proved totally unable to withstand the onslaught. The vaunted unions were no match. While union member- ship did increase during the postwar era, the growth in capital mobility fatally undercut their leverage. When the oligarchs politically mobilized, creeping capital mobility put the wind at their back. The more the oligarchs pushed politically, the more the obstacles to capital mobility crumbled, and the more mobile capital became, the more effective the pushing became. It was a losing game for labor, and the game is still being played to this day.

This hasn’t stopped theorists from trying to imagine ways of reversing the trend. Thomas Piketty argues that if we could get governments to club together and agree on common economic policies, the oligarchs would lose their ability to pit countries and states against each other. He calls for a global wealth tax [16]. The trouble is that global political coordination requires that many countries elect—all at the same time— politicians who are interested in pursuing this strategy. If some countries don’t have governments that are interested, those countries can take advantage, offering oligarchs and corporations special deals to relocate jobs and investment. In each country, oligarchs are heavily politically mobilized, preventing the election of governments that might be interested in Piketty’s strategy.”

Of course, here Stevenson’s project could be positioned as one that is banking on the possibility for such a “club of governments” that could “agree on common economic policies” and fight against any countries which fail to align with this vision.

So now to boil this down to its core, in the microcosm of political conflict, as read through the lens of Benjamin and Stevenson, we have something like:

Carl Benjamin: “Because of the Labour Party we decided to get very progressive and very diverse, i.e. privileging liberal multiculturalism for its own sake at the expense of the native inhabitants of England”

Gary Stevenson: “The Labour Party needs to fix the economic problem, and they need more class representation, i.e. stop focusing on woke social issues and start to build a national and international coalition to reform taxation.”

From my dialectical analysis, I am trying to find a way through the “most doomer” perspective of our situation, and at least think about what would be the condition of possibility for the build up of a coalition that includes within itself the seeds of the project that Stevenson is forwarding in the UK (and figures like Bernie Sanders are forwarding in the USA). Is it totally out of the realm of possibility for a Stevenson led reform of the Labour Party, and for a Sanders led reform of the Democratic Party, towards the establishment of an international coalition, or “club of governments”, that can “agree on economic policies” towards a “global wealth tax”? I do not say that this is the only path, but it seems like a realistic path, and even the most realistic path, given the forces that we have to work with on the contemporary horizon. In that spirit, what is to follow is my reflection, derived from a dialectical engagement, for how a “reformed Labour Party”, or a general international left, should think about the emergence of the populist right, if we are to “win them over” to what we might perceive as the “real issue”.

Here I am once again going to bring to your attention the Marxist distinction I have been centring throughout this analysis: the gap between the individual’s real life in society (under the logic of capitalist industrial production), and the political life of the citizen of a state (what we could call the dominance of bourgeois society). Here, on the side of the citizen of a state (for example, those who either work for or who are aligned with the Labour Party, or the Democratic Party, or the European Union), we have a tendency to be either painfully unaware or paternally disapproving, of the actual cognition and aesthetics of the “real working man”. To simplify to the extreme: liberal intellectuals trained by the universities of the state, tend to view the cognition and aesthetics of the real working man as xenophobic, defensive, and ethno-nationalist. While liberal intellectuals trained by the universities of the state attempt to embody a view that “rises above” the real working man’s xenophobia, defensiveness, and ethno-nationalism, it at the same time alienates the very people that are the real foundations of the whole society. Here we should remember what Marx said about the commoners or workers (those who lack property and are in need of immediate labour):59

“The sole characteristic thing is that the lack of property, and the class in need of immediate labour, of concrete labour, forms less a class of civil society than the basis upon which the spheres of civil society rest and move.”

In other words, what we tend to find about liberal intellectuals trained by the universities of the state, is a kind of mental defence of the point of view of bourgeois capitalists circulating capital (i.e. “capital mobility”), and a mental rejection of the very “basis upon which the spheres of civil society rest and move”. This means that even if liberal intellectuals know that immigration is a symptom and a wedge issue used by right-wing populists, if we are to form political organisations capable of dealing with the issue of capital mobility on an international level, we will need the support of people that we may perceive to be “xenophobic, defensive, and ethno-nationalist”. To be direct, we would need the abolition of the tendency of liberal intellectuals trained by the universities of the state, to stop censoring discourse along “woke lines”. Marxist political theorist Daniel Tutt calls for an end to such discourse, stemming from what he calls the “censorial left” unable to see the “working class” as an “agent of social emancipation”, in the recently published works Flowers For Marx, which points :60

“The rise of a censorial left arises not only due to its entanglement with both the state and private interests. A historical analysis of the New Left of the 1960s-70s and its move away from the working class as the agent of social emancipation, […] must also be factored into the wider situation. Its retreat from the working class contributed to a growing incapacity to achieve the class independence Marx posited as necessary for the cultivation of the worker’s counterpublic. […] A dejected left, sheltered from the working class and operating within private liberal institutions will inevitably adopt an internal culture characterised by backstabbing, careerism and grievance.”

Tutt also points towards the Early Marx, pre-1845, relevant to our focus on the Critique of the Philosophy of Right, in order to find “valuable political lessons” for this struggle:61

“How should we approach the thought of the young Marx, the budding revolutionary journalist, moving around between socialist parties not entirely sure of his political direction, and philosophically caught within the idealist trap of Ludwig Feuerbach? There has been a tendency to ignore this period in the wake of Louis Althusser’s influential notion of the “epistemological break”. According to this periodisation, after the Theses on Feuerbach and The German Ideology in 1845 Marx breaks from the naive humanism of Feuerbach and all forms of left-Hegelian thought. […] I want to argue that Marx never entirely abandons humanism, Hegel or philosophical principles as Althusser suggests. To be sure, the novelty of Marx’s rupture with left-Hegelian thought is significant. But we must not abandon the crucial pre-1845 thought of Marx, especially given that it entails valuable political lessons.”

Tutt continues:62

“[Pre 1845] Marx was so resolutely opposed to censorship that he questioned whether his liberal peers really believed in freedom of the press because they uncritically followed the censorship rules. This was a problem that was not only a problem for journalism, it impacted the philosophy of liberalism itself as it gave rise to what I call the “censorship complex” — a complex in which the humanist ideals of freedom and liberty cannot be realised as philosophical principles in the wider public sphere. […] We can understand the problem of censorship for Marx as placing a fetish or a cover over the true ideals that underpin political values. […] This defect leads to a crisis in civic education and social reality. The liberal intellectual cannot propagate a vision of collective social reality when they are beholden to the private whims of capital backed up by the state. Marx’s argument is that the bourgeois public sphere, dominated by censorship, stunts public education and undermines the enlightenment project upon which liberalism is founded.”

This emphasis that Tutt is making on the tendency of the liberal university and society towards the censorship complex is absolutely central to opening up the capacity to think again on the level of what this article has been demonstrating: the need to think the unity of populist right and populist left movements. The liberal intellectual can obviously fall into the temptation to censor and scapegoat someone like Carl Benjamin (i.e. Benjamin is just a racist, bigot, xenophobe, etc.); but the liberal intellectual can also fall into the temptation to censor and scapegoat someone like Gary Stevenson (i.e. Stevenson often speaks of how liberal economists fundamentally censor core issues of economics related to inequality). Here, following Tutt, we should dare to look precisely at the discourses being censored by liberal universities and societies, where we will find many extreme positions that challenge the political status quo. If we do not bring these extremes to reflection, we could risk falling into civil war; but if we bring these extremes to reflection, we may be able to actually work towards a real reform.

If we are going to be able to work towards real reform, we will need to break the separation between the liberal intellectual and the working class. Stevenson, as a new voice for the let, as in his work made a real attempt to frame himself as not only partisan to the left, but also broadly speaking, capable of speaking to all classes: lower, middle, and upper class:63

“I want to send out a message to the working class that don’t trust the middle class. Listen I come from a working class background and now I move in some fancy circles when I have to. And sometimes I don’t trust them either. I know they can be dick heads and annoying. You aren’t going to get out of this without their support. I know you are the guys on the front lines getting hurt, but if the working and middle class cannot stand together then the rich will win. […]

To the middle class that don’t trust the working class. Listen, I know you are not on the sharp end now, but once the rich have taken all the wealth of the government and poor, whose wealth are they going to take next. Don’t be stupid. […]

If you are rich, or if you are super rich, you have a nice life. I have seen how you guys live. It is nice, you get a lot of luxury and it’s cool. But by pushing this further and further, and taking more and more and more, you are aggressively destabilising the economy and political systems of the countries in which you live in, and give you extreme luxury. What the fuck are you doing? It’s enough. […] You’ve got enough, if you keep pushing, you will destabilise the countries that give you this enormous amount of wealth. Look at what has happened in history, look at what has happened in the 20th century. I am not trying to redistribute wealth away from the rich, I am trying to stop the redistribution that is bankrupting ordinary people.”

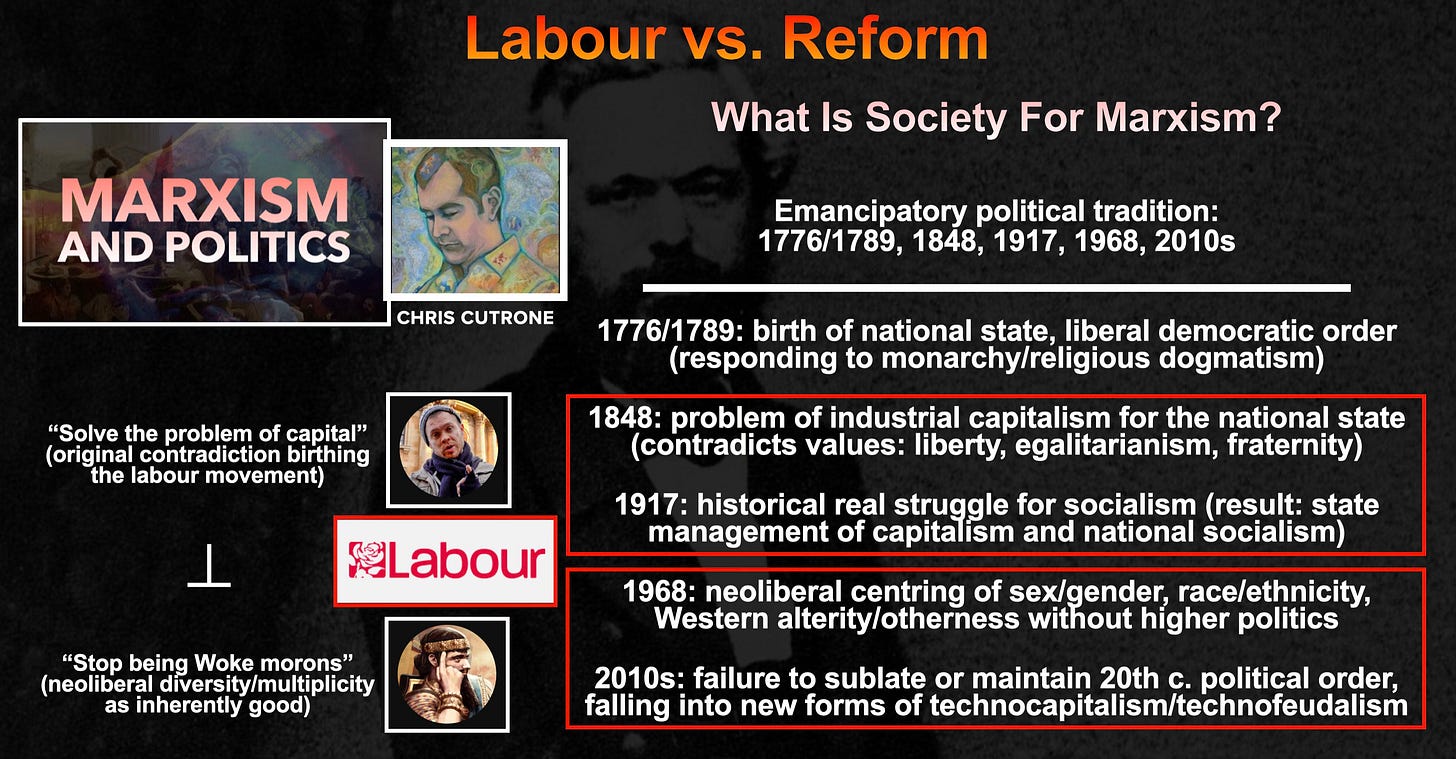

I will end by saying that Marxist theorist Chris Cutrone’s implicit historical framing of emancipatory politics, clearly visible in his most recent work Marxism and Politics, has been indispensable for me in thinking about contemporary conflicts between the populist right and left.64 For Cutrone, we can think about the emancipatory political tradition as operating along the following fault lines:65

1776/1789: birth of national state, liberal democratic order (responding to monarchy/religious dogmatism)

1848: problem of industrial capitalism for the national state (contradicts values: liberty, egalitarianism, fraternity)

1917: historical real struggle for socialism (result: state management of capitalism and national socialism)

1968: neoliberal centring of sex/gender, race/ethnicity, Western alterity/otherness without higher (socialist) politics

2010s: attempt and failure to sublate or maintain 20th century political order, falling into new forms of technocapitalism/technofeudalism

Here I would propose that we can think with this structure as a historical fractal memory of the collective political social body, and see both Benjamin’s populist right concerns and Stevenson’s populist left concerns located very precisely at different levels of the historical fractal:

Stevenson is located in the 1848-1917 window where the problem of industrial capitalism for the national state appears, and where the historical real struggle for socialism appears

Benjamin is located in the 1968-2010s critique where neoliberal centring of sex/gender, race/ethnicity, Western alterity/otherness without higher politics leads to catastrophic social decline into technofeudalism

Finally, I want to bring attention from this microcosm of the issue towards its international dimension, where I think we can see the same patterns repeating themselves in the UK, clearly active as well in the USA, and other Western countries. I think the pattern is something like the following:

Ordinary people (“ordinary consciousness”) becomes overwhelmed by globalism driven by technocapitalism (national populations, cultures, rituals are obliterated)

Nation states designed for the 19th century are unable to resolve contradictions of capital/labour and become captured by the “Capital Nation-State”

The traditional two-party system starts to crack: Conservatives have nothing left to conserve; and liberals become vague empty universal humanists

Right-wing reformists rely on scapegoating racial/ethnic otherness, approaching the problem as a cultural one, as opposed to an economic one

And left-wing internationalists focus on technocapital as cause of inequality but cannot practically form unified bodies to regulate it

If we are to address this pattern, internationally, we will need to start thinking about very concrete polarisations, which are currently manifesting in the forms of the populist right and populist left. But if we do not think these forms dialectically, if we are unable or unwilling to look at the cracks, then we will not be able to think with the negativity of our moment, and actually build the capacities to deal with it.

This year at Philosophy Portal we will be taking our time with the writings of the Early Marx (1840s), with the opening of the course taking time to give special focus to Marx’s Critique of the Philosophy of Right. You can find out more, or get involved in this initiative, at the following link: Early Marx 101.

Learn more or get involved: Early Marx 101.

For more on Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, see: Philosophy of Right.

For an expanded commentary, see: Critique of the Critique of the Philosophy of Right.

My first attempt at approaching this issue can be found here: Last, C. 2020. Global Commons in the Global Brain. In: Global Brain Singularity: Universal History, Future Evolution and Humanity’s Dialectical Horizon. Springer. p. 107-147.

How to Stop Europe’s Collapse: Learning from Germany's Mistakes | Christine Anderson | EP 559. 2025. Jordan B Peterson. (link)

Perhaps the leading theorist of this idea is Renaud Camus’ and his idea of the “Great Replacement”, see: Camus, R. 2024. The Great Replacement: Introduction to Global Replacism. Independently Published.

See: Sargon of Akkad and Akkad Daily.

See: Garys Economics.

I am using these terms “far right” and “far left” from the point of view of the “center” as some form of “constitutional monarchy”, “Parliamentary Republics” or “Presidential Republics”, with “far right” pointing towards a form of “national socialism” and the “far left” pointing towards the form of “international socialism”.

Ibid.

See: Restore Britain.

“2.5 per cent tax on assets over £10million”, see: Gary Stevenson and campaigners want a wealth tax: What is one and would it really work? (link)

See: Paul Kingsnorth: "Against Christian Civilization" | 2024 Erasmus Lecture. 2024. First Things. (link)

There seems to be a broad consensus that the biggest problem for this tax reform would be the dimension of international coordination for a wealth tax, since if it were only done on the level of the nation, the wealthiest could simply leave the country and move their resources and assets elsewhere. The ideal of a global wealth tax was proposed in economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, see: Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press.

Ibid.

Even if this theological dimension is not always explicit in the sense that someone like Carl Benjamin perceives himself as a secular populist-right wing reformer

e.g. actually existing Afghanistan. See also: I’ve Worked with Refugees for Decades. Europe’s Afghan Crime Wave Is Mind-Boggling. 2017. The National Interest. (link)

Of course, this is all framing the tensions between Israel and Palestine, with Israel’s state politics being generally linked by the left to a genocidal terror; and with Israel’s state politics being generally linked by the right as a justification for ethno-nationalism against the threat of Islamic theocracy.

For Benjamin, it is something like they serve the EU “techno-crats” who are “architects” for a “post-national Europe”.

See: Census maps.

See: Reform would win most seats in general election, in-depth poll suggests. 2025. sky news. (link).

Ibid.

Marx, K. 1844. Critique of the Philosophy of Right. p. 42 (§ 294).

See: Restore Britain.

Stevenson, G. 2024. The Trading Game: A Confession. Allen Lane.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press. p. 515.

Slavoj Žižek: Democracy and Capitalism Are Destined to Split Up | Big Think. Big Thing. 2015. (link)

Studebaker, B. 2023. The Chronic Crisis of American Democracy. palgrave macmillan. p. 23.

Ibid. p. 16.

Marx, K. 1844. Critique of the Philosophy of Right. p. 71.

Tutt, D. 2025. Foreword. In: Flowers For Marx. Revol Press. p. xxv-xxvi.

Ibid. p. vii-viii.

Ibid. p. x-xi.

Cutrone, C. 2024. Marxism and Politics: Essays on Critical Theory and the Party 2006-2024. Sublation Press.

For a full reflection on this, see: Marxism and Politics.

Great piece. I would like to see more thinking about the split in the Working Class itself, which to my knowledge Marxists have underestimated. Namely that the immigrant working class has a plan B, somewhere to go back to, (or else has already fundamentally been uprooted and become a global nomad), where the native working class doesn't. This was probably less of an issue for Marx and the early socialists due to global labor and migration patterns being simpler. The assumption is often "there is ONE working class who are split by cynical ideologues instead of recognising their common interests", the challenge presented by the 21st century is that often these "common interests" seem as much the dream of middle class left wing ideologues projected onto the working class. And ironically these middle class left wingers recognise themselves more in the immigrant working class than in the native working class, due to having plan Bs and global mobility, ergo the Bob Vylan spectacle.

Brilliant we can go back all the way to Martin Luther and reform will always f*** over labor from the very start of modernity