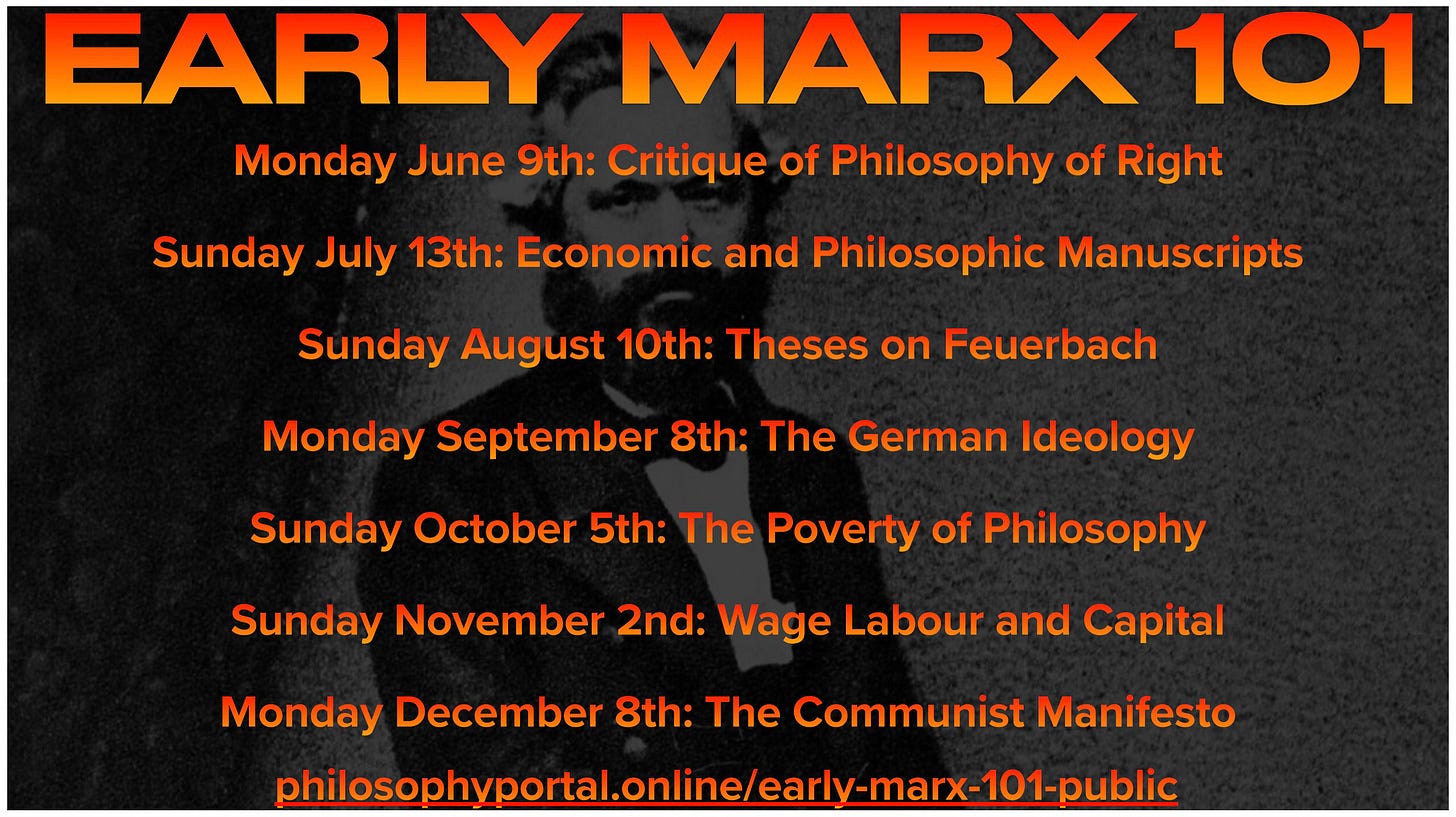

This year at Philosophy Portal we will be taking our time with the writings of the Early Marx (1840s), with the opening of the course taking time to give special focus to Marx’s Critique of the Philosophy of Right. You can find out more, or get involved in this initiative, at the following link: Early Marx 101.

Marxism became salient for me around 2013/14. Before getting into Marxism I spontaneously identified as something like a “left liberal”. While Marxism and the problems it identified became salient for me, my relationship to conventional Marxist signification or Marxism itself as a signifier, was and is extremely complex.

To start, when I say Marxism became salient for me, what I mean is that, on a personal level, I had become aware of the contradiction between labour and capital. At the time, and still to this day, I would/will get frustrated about how capital does not track my labour (or work) meaningfully, or how the labour (work) I find meaningful is hard to track with capital. Of course, many people feel this contradiction, and many take it as a given fact of life, but for someone interested in Marxism, there is a sense that something political that can be done about it, that the problem is historically conditioned, and can be changed. For a Marxist, there is the idea that not only does the contradiction of labour/capital conflict with our capacity to live a life in service of our true aims and desires, but that our life does not have to be this way.

In the process of wrestling with this contradiction and way of thinking, one encounters a major shift in understanding the way our identities are conditioned by the frame of the liberal democratic state, and the logic of capital. One starts to realise that, no matter what field we happen to find ourselves in, that field seems to be in some way conditioned by the political-economic order within which that work is being done. To be specific, this structure overdetermines the way our knowledge is produced, and the way the form of our thinking is unfolding.

For most working within the liberal democratic state under the logic of capital, there is a way in which we can spontaneously in our ideology come to see (and enjoy) the liberal democratic state under the logic of capital as the “end of history”, as Žižek has made clear throughout his career, and in response to political theorist Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man.1

The spontaneous ideology assumes something like history has now been completed, as if the liberal democratic state were itself “eternal”, and that there would be no further significant political disruptions, regressions, or revolutions. What we find here is often a presupposition or even an explicit desire for all countries around the world to gradually adopt models of the democratic liberal state. In the first decades of the 21st century, this presupposition and desire has taken on characteristics to include the model of Scandinavian states on social policy (e.g. Sweden, Finland, Norway).

I certainly held many of these presuppositions in the earlier years of my personal political journey. The dominant political narrative in my identity was something like a “left liberal with democratic socialist aspirations” (as a type of telos). This narrative represented my understanding of not only practical beliefs, but also my sense of truth and justice. I presupposed that what I would experience throughout my lifetime was something like a steady progress within liberal democracy in the capacity to work with the logic of capital towards something more socialist. What “something more socialist” might have looked like to me at the time was generally a more equal society in many dimensions, including expanded opportunities for labour, upward mobility for more and more people, well-grounded floor for basic needs, e.g. food, shelter, security, etc.

As one might predict for someone with this general political sensibility, there was quite a lot of excitement and anticipation about the possibilities of the most powerful nation state on the planet, the United States of America (USA), to elect Bernie Sanders, a literal democratic socialist, as a candidate for the presidency. However, after the Democracy Party of America failed to nominate him, and arguably sabotaged this possibility, I experienced a general disappointment and withdrawal from politics. One might even say that my political “transcendental illusion” had been shattered.

In terms of the direction of left liberal politics, my own withdrawal from interest in the political landscape coincided with the rise of “Woke ideology” or “political correctness”. I interpreted this rise as a severe regression where cultural concerns about gender and race appeared to dominate the conversation over and above concerns of capital domination as it relates to democratic socialist movements. In withdrawal, I simply watched as the political dialogue seemed to become captured by both these cultural concerns, as well as the right wing counter-cultural reaction to it (something I would like to both Donald Trump’s first presidency, as well as the rise of clinical psychologist Jordan B. Peterson to international superstardom). While I recognised that this counter-cultural reaction made important critiques of what had become of the left, I at the same time thought it was a shame and a cultural distraction from the core political mission orbiting the contradictions of capital and labour, and which I had hoped a democratic socialist party could address directly and substantively.

More recently, political theorist Chris Cutrone reflected to me, that the reason the whole democratic socialist project failed, and specifically the Bernie Sanders presidential candidacy, was and is because there is no desire within capitalist politics (i.e. a liberal democratic state under the logic of capital) for a real democratic socialist movement. For Cutrone, capitalist politics is bound to destroy or thwart any attempt at democratic socialism as it undermines the logic of capitalist politics itself. For Cutrone, this very fact alone forces us back to Marx, in terms of forcing us to think the limits of the democratic liberal state, what is possible and what is not possible within it, as well as what it would involve to think and act beyond those coordinates.2

While Sanders presidential candidacy failed, what arguably broke the frame of the liberal democratic state, was the first and now second terms of Donald Trump’s presidency. I think it would be misleading to refer to Trump’s presidencies as either fascist or monarchist in orientation, but certainly there are aspects of his presidencies which do not conform to normal neoliberal party politics. This combined with a significant rise in discontent about the current forms of our political organisations, makes Žižek’s critical thinking about Fukuyama’s thesis prophetic. Today, as since 2016, it has become far more common for people to start thinking it a necessity to go beyond the coordinates of the liberal democratic state. In this context many people think about what a “post-liberal” politics and society would look like. Here ideas of monarchy, theocracy, and national socialism have become more popular. However, I find that many of these ideas, branding themselves as “post-liberal”, are actually just “illiberal”, i.e. not raising the contradictions presented by liberalism to a higher order, but actually regressing to a pre-liberal state. In this territory, I myself tend towards the idea of the sublation of liberalism, as both a way to make sense of my previous political orientation, as well as to make sense of how I am trying to reconfigure my political orientation.

The question is whether or not the sublation of liberalism is still a tenable political proposition, or is it completely deluded?

To address this, I have found myself reflecting more and more on my historical-personal encounter with Žižek as a thinker, around 2013/14, because this conditions the way I had started to think, and still to this day think, about Marxism. Thus, my interest in Marxism did not only come from my personal recognition about the contradictions of labour and capital, but also came from my interest in Žižek’s unique perspective on the topic. Žižek himself is a strange type of Marxist; you could even say that many diehard or fundamentalist Marxists would see Žižek as a non-Marxist. Stated positively, they would see Žižek as a Hegelian.

In order to clarify Žižek’s position and motivation with inverting the relation between Hegel and Marx, as well as the framing of my own introduction to Marxism, consider the following quote from an interview Žižek gave in 2013 as part of a promotional tour for Less Than Nothing, which I think captures his philosophical aims well:3

“My main concern is the deadlock of the Left in mainstream global politics. We all feel that there is some potential crisis looming, that something has to be changed. But there seems to be no capacity of the Left to formulate again a global project, the way the Left did it 100 years ago, with Communist Revolution. We have to return to the very origins. Was it already something in Marx that was not developed enough, and not that Marx was responsible for it, but which opened up the space for later Stalinism. We have to ask radical questions.”

This quote is both clear and clarifying, because it frames well how Žižek’s main concern throughout his philosophical work is political. Here the difference between Marx and Žižek is that, while Marx is interested in moving philosophy into emancipatory politics (as a reaction to Hegelianism); Žižek remains fully philosophical, from a Hegelian perspective, while keeping a focus on emancipatory politics. Consequently, we can more easily understand here how Žižek’s philosophy allows us to access the unity of “Hegel-Marx”, or the height of modern philosophy and emancipatory politics, as a “non-orientable surface”, as opposed to a linear one-sided directionality.4

I think that Žižek’s philosophy in this context is also well situated in relation to Chris Cutrone’s affirmation of the “Death of the Millennial Left”.5 Cutrone emphasises that the Millennial Left did flirt with state politics on the level of socialism (e.g. Bernie Sanders), but after its failure, now finds itself in a recessive dead state, lost in the capitalist jungles, unable to assert a new orientation. In this sense, Žižek’s call to go back to the “very origins”, and Cutrone’s call to go back to thinking the original problems presented in Marx and Marxism, is about going back to first principles, while we remain in an impotent void-state regarding emancipatory politics.6

In the context of my political journey from 2013 to 2016, the notion from Žižek that further deepened my engagement with Marxism from a Žižekian angle was the axiom “don’t act, just think”.7 This came at a time, around 2015, when I had fallen quite deeply into a Marxist activist identity. This identity proved to be way too confident in its illusions about changing the world. In the cracks and failures of that identity, doubling down on philosophy became my direction, and that direction ultimately led to the construction of Philosophy Portal and its motivations. Here I think that the form of Leftism I started to embody on a personal level involved a type of deep mourning about the loss of its object, i.e. a meaningful democratic socialist project within liberal democracy, and capable of raising it above the logic of capital. In this process, I have come to experience other “progressives”, or “left-liberals”, or “democratic socialists”, as having failed to go through a sufficiently deep grieving process about how deep the failure is, and how thoroughly we have lost any meaningful political object. As a result, much of progressive, left-liberal, or democratic socialist politics becomes even more disconnected from the real movement of the counter-culture, which again, has turned more conservative in nature (even Žižek now calls himself a “moderately conservative communist”).

The challenge here is simply another affirmation, following the aforementioned Žižek quote, of how badly we need to go back to first principles, and how deep the political and philosophical work required actually is.

The most basic philosophical presupposition in Marxism is that a socialist or communist form of politics not only can transcend/go beyond liberal democracy in its nation state form, but necessarily must due to the inherent contradiction between labour and capital. This presupposition has historical political actuality, starting with the Russian Revolution in 1917, which opened a failure that still haunts our political imagination today in terms of our capacity to think a politics beyond the logic of capital. In significant 20th century Marxist political imaginaries, the idea that it is “easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”, has become common place, from Fredric Jameson, to Mark Fisher, to Slavoj Žižek.

What this crisis of the political imaginary after the Russian Revolution represents is basically our inability to protect the interests of labour from the domination of capital, and the way that domination reproduces inequality and exploitation. This inequality and exploitation has been traditionally described as a class conflict between the “bourgeoisie” and the “proletariat”, the “liberal elite” and the “working class”, or the “1%” and the “99%”. In the spirit of going back to first principles: how relevant is this way of thinking for us today? Of course in the first decades of the 21st century the conversation about the “1% vs the 99%” exploded, especially during the Occupy Wall Street movement. This rhetoric still basically holds together the messaging of Bernie Sanders and his democratic socialist push for a presidential candidacy. But how real is that thinking, or how alive is that thinking, broadly speaking, for the “working class” today?

Michael Downs of

blog, and author of Timenergy vs. Capital,8 has emphasised in several podcasts that the real of working class people today wants nothing to do with the identity markers of Marxism or proletarian consciousness, at least not explicitly. Perhaps class analysis or proletarian identity have become irrelevant to actually existing party politics? Perhaps what was the counter-culture of the 1968 left was neoliberal in its core (as a symptom of failed socialism in the first half of the 20th century), and in becoming the mainstream culture, we have totally lost the historical memory of what leftist politics is supposed to be oriented around?While the Marxist orientation for politics is relatively impotent, the “national socialist” forms of party politics, often driven by a form of nativist ethno-belonging, seems more active and real. In this context, it might be more likely to meet working class individuals in the West, who are concerned about immigration, ethnic identity, collapsing reproduction, and so forth. While anti-corporatism and anti-globalism are typically also relevant political sentiments, many people in the working class see the contemporary left as “liberal corporate globalists” architecting a plan for “diversity, equity, inclusion” (DEI), which is antithetical to their concerns about the loss of national or ethnic identity, coupled with a feeling of practical unrootedness, being unable to either support a family or build a local community, given severe economic constraints and eroding institutional support. One might even say that the working class would have to be “Christ-like” in its openness to the other in order to rise to the political and social challenges that are expected of it today (and indeed today we do see a “surprising return” of Christian belief among both the working class and the rapidly proletarianising middle class).

But as all this relates to politics, I am trying to emphasise that, among the contemporary working class, we are more likely to see an inverse politics of identity, where the DEI structures of liberal globalism, are transformed into a counter-cultural force framing the issue as “White Europeans” versus “Black and Brown bodies”. This re-framing is also taking place in the break down of the “post-World War II consensus” that fascism, or “national socialism”, is the worst evil (through the vectors of both the symbols of “Hitler” and the “Nazi party”). Here I do not want to over-exaggerate the relation between White Western working class individuals wanting to decrease immigration and re-solidify an ethno-belonging with outright neo-Nazism, but the connections are legitimately present, and the framing can lead one in that direction. The concrete desire appears to be motivated by a political will to enforce a strong limit on the asymmetrical flows of global migration from the “Global South” (Africa, Middle East, South Asia, Latin America) and the “West” (Europe, North America). Of course, this becomes coded in “Black and Brown bodies” (Global South) vs. “White bodies” (West), even if a simplification. In the most extreme, what makes this framing even worse, is that the cause of the immigration and the erosion of local identity is located, not in global capital looking for cheap labour (with the liberal state being unable to stop it), but in the figure of “The Jew” as trying to architect the downfall of the White Christian race.

For Marxism, it is not only that the framing of the problems of national socialism are immoral (as DEI leftist might emphasise), it is that they are not actually identifying the correct problem. For Marxism, this type of thinking is actually a degeneration to illiberal or pre-liberal thinking, and not towards a post-liberal thinking, because the analysis of capital is not centred around “ethnic substance” of the “human agents” who are merely capital’s “character masks”. Instead analysis is centred on the actual dynamics of class internationally because any national solution is bound to run into the problem of the nature of capital: it is global. Consequently, any response to the logic of capital, is likely to have to match the scale of that problem.

The problem of scale, the relation between the local (family-community) and the global (state-international realm of states), when it comes to thinking politics today, is an enormously disorienting and confusing topic. And while I am obviously framing the move or the drift to national socialism, or potentially new species of fascism, as dangerous, I also want to state explicitly that I am also well aware that Marx and Marxism is dangerous. If you are not philosophically armed, Marx and Marxists texts can be misleading and misguiding, and even life destroying. As a result, I have always stayed away from identifying explicitly with Marxist language in my previous political writings, even if I was exploring Marxism and communism with a deep interest. For example, my most explicit writings on politics come from a paper I originally published in the journal of Technological Forecasting and Social Change, and which was reproduced in my doctoral thesis, Global Brain Singularity, titled “Global Commons in the Global Brain”. The abstract reads as follows:9

“The next decade (present to 2020-2025) could be characterised by large-scale labour disruption and further acceleration of income and wealth inequality due to the widespread introduction of general-purpose robotics, machine-learning software/artificial intelligence (AI) and their various interconnections within the emerging infrastructure of the ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT). In this paper I argue that such technological changes and their socio-economic consequences signal the emergence of a global metasystem (i.e. control organisation beyond markets and nation-states) and may require a qualitatively new level of political organisation to guide a process of self-organisation. Consequently, this paper proposes and attempts to develop a conceptual framework with the potential to aid an international political transition towards a ‘post-capitalist’ ‘post-nation state’ global world. […] In the integration of Global Brain theory and Commons theory this paper ultimately argues that an appropriate international response to the emerging technological revolution should include the creation of networks with both automated and collaborative components that function on ‘Global Commons’ logic (i.e. beyond both state and market logic).”

What I want to bring to your attention in citing this abstract is the way the paper both attempts to go beyond state and market logic, while at the same time, it avoids using the word “communism” (or even socialism) to achieve this. Instead I started to rely on “commons theory”. I still feel an aversion towards using the word communism in any strong identification, but the term “commons” was used explicitly here, which is perhaps most strongly associated with the work of Nobel prize winning political theorist Elinor Ostrom.10 I think I started to use the word “commons” instead of “communism” because the political issues I anticipated us facing when I originally wrote the paper in 2017, were not so much issues of “community”, but of redistribution of resources given a new technological possibility space. I state explicitly in the paper that perhaps we should consider a move from “communism” to “commonism”, in the sense of a shift from living in shared communes (which risks a illiberal regression), towards thinking about the general distribution and management of shared resources (where liberalism could be more obviously “sublated”).11

Now I would rethink the paper “Global Commons in the Global Brain”, if I could go back to it. I still fundamentally agree with the paper in the sense that I do think in the 2020s we are having this disruption of labour and inequality due to massive technological developments. But I would rethink specifically the way I am trying to deploy the relationship between Global Brain theory and Global Commons theory. This would involve a new framing for how I was thinking about the commons. In the paper I use the term commons as a “beyond” of both market and state, and as a “global” all-encompassing category for “global commons problems”.12 But now I understand the commons as much more of a “grounding” and an “underneath” of both the market and state.13 In that sense, the way I am using “Global Commons” in the paper is a bit like a “big Other” (replacing the big Other of a communist command and control economy with the “Global Commons”).

In contrast to this approach, where I have come in my own studies, and in my own process in philosophy, is to put the commons on the level of the family and community, rather than a global organising paradigm. Unfortunately, and admittedly, this does severely limit its capacities to really deal with the issues of global capitalism because it is precisely locating the commons as a useful category for more local contexts. To be fair, commons theorist Michel Bauwens work points towards the use of the term “cosmo-local”. For Bauwens:14

“cosmo-localism describes the dynamic potentials of our emerging globally distributed knowledge and design commons in conjunction with the emerging (high and low tech) capacity for localized production of value.”

This means that while the commons cannot function as a political “big Other” to deal with global capitalism, it can attack the problem from below in a multi-local web or network. This does seem to be an important piece of the puzzle, and one I will certainly keep exploring and attempting to embody in my contexts, while at the same time searching for new ways to connect these ideas to the higher order domains of politics (e.g. states and the inter-relations between states).

Towards finding these connections in local context, the commons seems best understood as a historical model for a contributive economy, which is trying to fill in the gaps and holes where the market and state break down or function poorly. Here building a commons is the equivalent to or in relation to building a civil society. Now there is this question of how would a grounded civil society, with a well-functioning commons, approach questions of society and the state in global capitalism more broadly? That is my current orientation: when I hear activists or theorists critiquing on the level of the state, I often assume that they are not well-enough grounded on the level of the commons, that is on the level of family and community.

Beyond this self-critique of my paper, I still basically agree with its orientation regarding the need for some sort of “automated/collaborative commons”. I think that these questions, as they relate to the state, have an automated component and a collaborative component. The automated component seems most relevant to questions of inequality and redistribution or management of abundance. But the collaborative component seems more related to questions of identity and immigration in the sense of grounding real human community (as opposed to living in a world where people are constantly unrooted and unable to root). In the context of my paper, I would frame the automation question to be before Global Brain theory, and the collaboration question to be before the Global Commons theory (or a Cosmo-Localism). In this sense I still think the relation between “Global Brain” and “Global Commons” as concepts could be useful ways to think about these political necessities. I would just hesitate from thinking of the Global Commons as a type of big Other that distracts from the necessity local work of the contributive economy. This is like me trying to catch my own “self-slip” in the symptom of not knowing what to do with Marxist theory, or being hesitant to confront it directly: it returns as a repressed form.

What would happen if we do not approach these problems of automation and the Global Brain, or collaboration and the Global Commons? I think that on the automation/Global Brain side the worst outcome would be something like a fully actual technofeudalism. On the side of collaboration/Global Commons I think the worst outcome would be something like a pan-national ethno-socialism. In a way, both of these outcomes are not so much future predictions, but more seeds that already exist in the present, if not full blown flora and fauna. In other words, even if in early forms, both problems are technically here now, and not to be actualised in some distant future.

These extended reflections and detours are ultimately building up towards my attempt at reconciling with how I relate to Marxism as a signifier. This avoidance is fair in the sense that it is really hard to engage with a signifier like Marxism well. It is hard to get involved in Marxism, and political theory on that level, and not sound like an idiot or actually be an idiot. I cannot stress this enough: it is hard to do it well. I want to strongly presence that engaging with these ideas takes time. I am not saying I can now do it well, but I have been in a process of trying to do it well. This article contains the fragments of that attempt.

I will start by saying that I experience the same fundamental feeling around “die hard” Marxists that I get around “fundamentalist” Christians. I elaborate in my book Systems and Subjects, that I think there is a structural-systematic overlap, in terms of the identity forms of “die hard” Marxist and “fundamentalist” Christians. This structural-systematic overlap has to do with the relation between the telos of World Communism and the Kingdom of God, which seems to orient cognition similarly.15 I think the basic issue I have is that they perform as if “they know” the “true necessity of history”. That is also why I gravitated towards Hegel and Žižek, because they do not perform as if they know the true fundamental necessity of history (that is the whole paradoxical point of Absolute Knowing). I think thinking itself can be shut down if we go too hard in the direction of presenting that we know the true necessity of history (like in a naive Marxist communism or a naive Christian kingdom).

My working assumption is that both die hard Marxists and fundamentalist Christians lack a philosophical grounding. I pointed towards this in my last article,16 proposing the non-orientable surface of “Luther-Hegel-Marx”, where the “die hard Marxist” would lose touch with philosophical grounding in a linear understanding of “Hegel-Marx”; and the “fundamentalist Christian” would lose touch with philosophical grounding in a repressed blockage between “Luther-Hegel”. I am trying to avoid that in thinking with “Luther-Hegel-Marx” as a “non-orientable surface” for “religion-philosophy-politics”. Ultimately, that is the point of this work at Philosophy Portal: to become the type of cognition that can think with Christianity and Marxism well. How many people can think with Christianity and Marxism well? Žižek is one of the only theorist I know who can do that well at a high level.

At the same time, we must re-state, that there is a total inadequacy of the mainstream liberal democratic centrist, either right or left, approaches. The dialectic of labour/capital, which is central for Marxism, does seem to be objectively exploding, and is the core issue of global politics when you boil it down to the basics. That is again why the culture war issues of “Woke/non-Woke” are just symptoms of this labour/capital dialectic, and distractions away from working with it.17 As technological singularity continues to unfold, I anticipate that will be more evident and obvious.

Consequently, I would also say that the tensions of labour/capital still motivate movements like democratic socialism or national socialism, even if solving the tensions of labour/capital, might not be possible within either of those frames. Certainly I don’t think it could be done in a national socialist frame. Whether it could be done in a democratic socialist frame remains to be seen, but again and following Chris Cutrone, it is hard to deny that it seems difficult for it to survive in the domain of capitalist politics. In the high probability that it will not succeed, what is more likely is that we see national socialisms, which may even link with things like religious moral solutions to ethnic and racial solutions (although these two dimensions do not always go together, and sometimes are internal anti-theses of the secular and religious far right). Here Marxism as a signifier becomes potentially hyper-salient for the inadequacy of both forms of socialism (democratic/national).

I should also state that there are figures who escape categories of democratic or national socialism, while still avoiding Marxism, that can generally be described as various forms of “accelerationist”. Here accelerationists tend towards the view that the intrinsic march of technological development will create an inevitable utopia or dystopia. But then accelerationists tend to avoid the actual political details of how either outcome will happen, or maybe tend to the view that politics is now irrelevant when it comes to the determinism of the hyper-technologically-mediated future. The view is something like “technology will make the utopia/dystopia”, and so we do not need to think the political choice dimension of the unfolding technological horizon. Or you can have people who think that technology will definitely create an immanent post-human reality, in which case you do not need to think the human political reality and the problems associated with human concerns (e.g. inequality/immigration, race/religion, etc.).18 Those are only concerns within a human reality. I would say I tend away from both accelerationist utopia/dystopia, as both are avoiding this crucial level of philosophy-politics, or even religion-philosophy-politics, and the arduous labour involved in the “Luther-Hegel-Marx” non-orientable surface.

Now finally building towards a more concrete attempt to articulate my relation to the Marxist signifier, I want to share a quote from

’s substack note, which I think articulates something worth tarrying with:19“It is more believable these days for someone to call themselves a Christian, as a real commitment, than it is for someone to call themselves a socialist. Christianity cannot be killed because it is not tied to a particular political movement; when the Berlin Wall fell, socialism died. People attempting to resuscitate socialism are not convincing. The dream is dead but the baby (history) is real, people. History keeps marching on, and amazingly, from the perspective of the 20th century, taking religion with it and leaving socialists behind. No wonder there is a move, in figures like Žižek, of tying the Holy Spirit to Communism, and acting as though it had always been there, attempting to rewrite the atheist legacy of the left as if it had been Christian all along. You know what made modernity great? New ideas like, in its own time, socialism. That’s what distinguishes great historical moments from dark, lackluster ones. If all we can do is keep recycling the old gods (Christianity, socialism, etc.) what kind of moment do you think it is that we are living in?”

I attempted to come up with a response to this note in order to struggle through my relation to the signifier of Marxism, because I do think Mittelstaedt is fundamentally correct that it is more in the culture today to meet Christians who are believable in their orientation than it is to meet socialists who are believable in their orientation. There really is this “surprising rebirth in Christianity” today,20 and there is also this “Orthodox-moment” (e.g. Paul Kingsnorth, Jonathan Pageau, etc.), which is fundamentally connected to the “surprising rebirth in Christianity”. This does signal a real commitment or re-commitment to Christianity, internal to “the West”. At the same time, I think Mittelstaedt is right to say that it is hard to find socialists who can forward a believable politics. Ultimately, this is why we have Cutrone’s “Death of the Millennial Left” and Varoufakis’s “technofeudal moment”, because socialism has collapsed, it is not believable. But the weird thing, at least to my mind, is that it very much seems like the problems we face demand something like socialism. So when Mittelstaedt suggests that the real of history marches on without a convincing socialist politics to deal it, I think he is pointing towards the fact that dimensions of global pluralism and the commons (e.g. immigration/identity) and techno-corporatism and the internet (e.g. automation/inequality), require some form of new ideas about socialism, or else we will have to deal with something like national socialism, or maybe just the brutal continuation of capitalist realism.21

Mittelstaedt clearly points towards giving up on the concept of socialism, but at the same time I still think that you can confront today quite believable national socialists (nativists/ethno-belonging). I think that is the blind spot of contemporary socialists: they are not willing to think where they need to think, they are not willing to look where it hurts, where it is uncomfortable, messy and dirty. Maybe we need to go back to the drawing board, to ground-zero, as I have emphasised through Žižek: maybe we do need a form of socialism that is connected to Christianity?22 Maybe this is something that we need to think through or else Christianity does get politically controlled and manipulated for more right-wing political agendas. Žižek’s philosophy does try to connect Holy Spirit to World Communism to form the foundation of Christian Atheism. While there are many elements in Žižek’s theopolitics that are old, the way he brings these old ideas together, he does seem to produce something surprisingly new and innovative. At least in my explorations, I have not come across anyone who frames theopolitics in the way he can and does.

Here I am reminded of Žižek’s self-introduction at a conference with the original Christian Atheist theologian, Thomas Altizer, when he said:23

“Despite always this new, new, new, maybe the most difficult and creative thing is truly to repeat what was already said.”

This is, from my perspective, one of the key differences between Žižek and Gilles Deleuze in philosophy. Whereas Deleuze tends towards the “creation of new categories/concepts”,24 Žižek is using old categories and concepts, but he is helping us see them in a new way. I think that is important.

In this context, my question for Mittelstaedt is: do we need new ideas or do we need to work through our history, and make our history itself more robust and believable? Two questions follow from this:

Can Christianity stand on its own as a response to global pluralism and techno-corporatism? (I think no, no way).25

Can socialism stand on its own without connection to its own theological ground (Protestantism)?26

The second question is a bit more ambiguous, but nevertheless absolutely crucial to think, if for no other reason that it is under thought. To be specific, I think socialists and Marxists have done a poor job of theorising here the “Theo-political” and even rendered arbitrary the origin of the ideas of communism from their theological soil in the Protestant reformation and also in German Idealism (which is the point of the Luther-Hegel-Marx non-orientable surface). Consider the opening of Žižek’s Christian Atheism:27

“Political theology necessarily underpins radical emancipatory politics”

This may not completely clarify my position in relation to the signifier of Marxism, but in a way it is at the same time exactly where I am at with it. I think that Marxism has to be connected more fundamentally to its own ground, which does involve breaks in religion and philosophy that are often perceived to be irrelevant to its own further unfolding. I do think that Žižek, if read deeply and well, still offers us a way to be “believable” socialists or even communists, or irrespective of the signification, offers us a way to continue working in the mess that is contemporary efforts in emancipatory politics.28 The point of the Early Marx 101 course, is to keep a fidelity to this possibility, and to return to the basics, to ask and frame hysterical questions for a perverted society.29

But I will not end the article here. I want to offer one last reflection, inspired by a conversation with Sean Mittelstaedt and Michael Downs as hosted on the “

Cast”.30 Downs and Mittelstaedt open the podcast discussing the social relations between narcissism and perversion, as inspired by the works of Christopher Lasch and Jacques Lacan. However, towards the end of the conversation, Downs frames what I think is a core problematic for those committed to thinking the future of emancipatory politics from the perspective of the real working class:31“You are not the dead beats living living off the system. You have worked your ass off your entire life and you still don’t have a future. If you aren’t pissed off about that then I don’t know what to tell you.”

Mittelstaedt agrees, responding:

“It is so easy for the culture to make it feel like it’s your fault. We do know that we could have done something different, made different moves. That leaves just enough of the door open that the ideology of the system can kick it down and tell you that you are a piece of shit.”

Downs then explains:

“Whenever they start doing the personal responsibility thing, let me ask you: how many people in this society do you know who have robust futures? I don’t know anybody that has a robust future. […] What so many people are feeling is this: there is nothing I can do to effect the way capital changes the world, and nothing I can do to effect the way capital keeps things the same. That’s where this sense of hopelessness and sense of resignation comes from. And if that’s true, then I guess I live my little life knowing I could have been more, and it’s that or suicide. I think that’s where people are at existentially.”

Downs view, which I take to basically be a “Doomer Capitalist” perspective, and one that leads to his self-proclaimed position in Capital vs. Timenergy as a “Burnout Marxist”,32 represents the position from which the “Capitalist Realism” of our contemporary society fails to formulate a “believable socialism”. From Downs:33

“Speaking only for myself, I would say that I’m some kind of Leftist without a Left. I still maintain a fidelity to certain universal and emancipatory Ideals that come out of the Enlightenment and Marxist traditions. That being said, I do not see any actually-existing Leftist movement that is truly paving the way towards a revolutionary future. I believe that capital is the essential problem we are facing, but also that there are no concrete solutions to this central issue.”

Even if Downs starting point for trying to find that believable socialism still seems to orbit the old Marxist distinction of capital and labour, although creatively reframed, in perhaps a very meaningful way, between capital and timenergy:34

“But my critical (Žižekian) engagement with Land’s work has a very specific aim: to come to a better understanding of the antagonism between capital and timenergy.”

I will just end by saying there is an emerging ecology struggling with this “socialist belief”. For example,

’s latest publications focused on “addiction and digital capitalism”,35 “the darkest timeline”,36 and “gothic capitalism”.37 Here we find an unbearable negativity that thought cannot sublate (work with), and which our alienated being cannot find happy separation (in fidelity to a true cause of our desire).38 In this context, perhaps we should double down on our fidelity to the Žižekian moment of philosophy in that, from my recent conversation with philosopher Mladen Dolar, the unity of thinking from the standpoint of an unsublatable negativity and a constitutively alienated being, is the whole core of what became the Ljubljana School.39This is again not to provide answers, but to basically leave you while pointing at the “black hole sun” of the Real where we must learn to dwell, to inhabit, if we are to really think again a believable socialism.

This year at Philosophy Portal we will be taking our time with the writings of the Early Marx (1840s), with the opening of the course taking time to give special focus to Marx’s Critique of the Philosophy of Right. You can find out more, or get involved in this initiative, at the following link: Early Marx 101.

Fukuyama, F. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press.

Here I recommend Cutrone’s text: Cutrone, C. 2024. Marxism and Politics: Essays on Critical Theory and the Party 2006-2024. Sublation Press.

Žižek, S. 2013. Livros 50: Menos que nada - Slavoj Zizek. UNIVESP. (link) (accessed: June 19 2025).

As I have expanded upon here: “Critique of the Critique of the Philosophy of Right”

Cutrone, C. 2023. The Death of the Millennial Left: Interventions 2006-2022. Sublation Press.

Hold on to that thought for the conclusion of this article.

In my discussions with Cutrone, he also says he has come to old a similar position, which leads to many Marxists thinking of him as a “quietist”, see: WHAT IS SOCIETY FOR MARXISM? (w/ Chris Cutrone).

Downs, M. 2025. Capital vs. Timenergy: A Žižekian Critique of Nick Land. Independently Published.

Last, C. 2020. Global Commons in the Global Brain. In: Global Brain Singularity: Universal History, Future Evolution and Humanity’s Dialectical Horizon. Springer. p. 107-147.

The term is also strongly associated with a fellow collaborator and political theorist

, founder of peer-to-peer (P2P), and who is a leading theorist on the theory of the commons. Bauwens will be leading a course at The Portal this September, see: The Commons: P2P and Civilisation Transition.In a recent session in The Portal

suggested that one of the crimes of modern neoliberal politics is that it has abused abundance, as opposed to using excess abundance to generate socialism (through proper management and redistribution), it is degrading both our human communities and the planet.This idea of “global commons problems” was explicitly inspired by Žižek, see: Žižek, S. 2011. Living in the End Times. Verso Books.

I tried to articulate various angles of this problem in a recent discussion with

, see: METAGELICAL AND EX-VANGELICAL (w/ Luke Freeman).See: Cosmo-Localism (accessed: June 23 2025).

See: Last, C. 2023. 3.1(c) — Necessity of Higher Consciousness from Negativity. In: Systems and Subjects: Thinking the Foundations of Science and Philosophy. Philosophy Portal Books.

See again: “Critique of the Critique of the Philosophy of Right”.

Very clear in the performative contradictions of Jordan B. Peterson.

Downs takes these forms more seriously in his work, see again: Downs, M. 2025. Capital vs. Timenergy: A Žižekian Critique of Nick Land. Independently Published.

See: Brierley, J. 2023. The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God: Why New Atheism Grew Old and Secular Thinkers Are Considering Christianity Again. Tyndale House Publishers.

Here see: Gieben, B. 2024. The Darkest Timeline. Revol Press.

If you go into the primary texts of Hegel and Marx, as well as the Young Hegelian milieu, this is not such a foreign or strange concept. This was also explored in the Christian Atheism course at Philosophy Portal, see: Christian Atheism.

Slavoj Žižek - Whither the "Death of God": A Continuing Currency? 2/7. Chomsky’s World. (link). (accessed: June 23 2025)

see: Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. 1991. What Is Philosophy? Columbia University Press.

And I think Christians who think that are completely deceiving themselves, enclosing themselves from the Real.

As is clear if you study specifically Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, and Marx’s Critique of the Philosophy of Right, and as I attempt to dialecticise in: “Critique of the Critique of the Philosophy of Right”.

Žižek, S. 2024. Christian Atheism: How to be a Real Materialist. Bloomsbury Academic.

Also the work of

is here important. Adam Turl, author of Gothic Capitalism, stated explicitly in his recent appearance in The Portal that one of his jobs as a writer and artist is to make socialism believable again, see: Turl, A. 2025. Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted From Heaven & Earth. Revol Press.See: “Mikey in the Mittle”.

Ibid.

Downs, M. 2025. Capital vs. Timenergy: A Žižekian Critique of Nick Land. Independently Published. p. 1 [/] 4-5

Ibid. p. 1.

Ibid. p. 5.

Watson, M. 2024. Hungry Ghosts in the Machine: Addiction, Digital Capitalism, and the Search for Self. Revol Press.

Gieben, B. 2024. The Darkest Timeline: Living in a World with No Future. Revol Press.

Turl, A. 2025. Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted From Heaven & Earth. Revol Press.

The Portal has been struggling with the texts from Revol Press this month, see: “Gothic Capitalism and Beyond”.

interesting topic to reactulize marx works. I read some of his texts lately after years of neglecting