Sacred Temple in Sublating the Profane

The importance of dialecticising religion, and becoming the eppur si muove itself

This month at The Portal we will be focused on the metaphysics of self-reference, or self-reference as metaphysics. We will be inviting guests Peter N Limberg of Less Foolish, Greg Dember of What Is Metamodernism?, and Alex Ebert of Bad Guru. To learn more or to get involved, see: The Portal.

I just returned from a great week of participation in Peter Rollins Wake Festival. The following is a reflection inspired by the launch of Rollins latest article “The Profane Temple” (link), but also a general reflection inspired by my contributions to the event.

What I see in Rollins’ work is a certain relation between everything and nothing. To be specific: everything seems to be at stake in the capacity to dialecticise religion on the level of a historical transcendental illusion. And when I say everything is at stake, I of course mean nothing is at stake.

Religion is an Absolute Idea that covers everything as its own sacred, not knowing itself to be a self-contradiction. Dialecticising religion means becoming the type of subject that can recognise the contradiction of the religious idea as covering over the profanity of nothing with everything. What our secular culture has yet to realise, has yet to integrate into its own being, is a reflection capable of reconciling with the profanity of nothingness, on its own terms, without trying to positivise it into a new sacred victory. What opens here is its own strange type of victory in the sense that one is opened to a different type of movement: one can start to work with the profane nothingness itself, and actually build new sacred spaces.

Here what interests me is the nature of this very movement, the nature of the subject that is capable of working with profane nothingness to build new sacred spaces. What is crucial is that we do not become subjects identifying with the new sacred spaces as the final thing, but rather identifying with the movement of transformation itself, the in-betweenness of everything becoming nothing, and nothing becoming everything. I think this type of movement and subject is what Rollins’s Church of the Contradiction is speaking to, and possibly also the type of movement and subjectivity it is capable of producing as a positive result.

Eppur si muove.

When we reify either the everything or the nothing we can get stuck into an unreflective death drive. What happens when we identify with the profane nothingness itself is that we can get caught in a non-dialectical reaction back to the emptiness of the material world and its superficial surface appearances which have not been properly mediated or worked through. What happens when we identify with the sacred space (whether of the other’s creation or our own) is that we can suspend an immediate illusion that may well have its place and moment in our life, but can quickly turn into something false when suspended as an actual eternity.

What we miss in both is our own subjective movement and its relation to objectivity.

Thus, what is most difficult is to understand what it means to be a subject that is doomed to movement. To be a subject that is doomed to movement is to be a subject that is not only a self-relating negativity, but is itself a division of itself, something of a repetition whose repetition is not of self-similarity, but self-othering. Thus, one cannot find either a full wholeness or a oneness, nor an empty nothingness or a void, but rather a movement between the two. Rollins ends “The Profane Temple”, his latest publication and collaboration with Alfie Bown’s Everyday Analysis pamphlet series, in a way that I think perfectly captures the metaphysical results of this idea:1

“The cure then does not lie in overcoming our self-division through some kind of reabsorption into the undivided Absolute, but rather in a full blooded affirmation of our own division as the very site of salvation, as the site where we overlap with the divide in the Absolute itself, or, more accurately still, where we realise that the Absolute is this divide.”

When Rollins speaks of becoming “reabsorbed” into the “undivided Absolute” he is talking about the wholeness or oneness that can become the transcendental illusion of everything in the religious idea, the everything that does not realise its own self-contradiction. This can obviously take the form of the actually explicit religious subject: the subject identifying with their “strong ego”, and without inner contradiction to, say, Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, etc.

However, this does not have to take the form of the explicitly religious subject. Alfie Bown of Everyday Analysis pointed out at the public launch of The Profane Temple, our culture often tries to supplement lack of explicit religious belief with the desire for wholeness in sports and music culture, especially as situated within a capitalist media ecology. Thus, the desire for wholeness and oneness can take the form of something most traditional religions consider to be profane, say, the subject identifying with their “strong ego”, and without inner contradiction to their favourite sports team or their favourite musician or musical competition.

From this observation, Bown suggests that we already find the “Church of the Contradiction” right in front of our eyes in the form of the unity of the “highest” being found in the “lowest”, “everything” being found in “nothing” (e.g. dreams of stardom and victory in the emptiness of reality tv show competitions and professional sports leagues). Thus, for Bown, he is led to the question: what do we need events like the Church of the Contradiction for? Is it not better to just leave this dynamic operating unconsciously rather than bringing it to reflection?

In Bown’s reflection, one gets the sense of Hegel’s famous axiom:

“The secrets of the ancient Egyptians were secrets for the ancient Egyptians themselves”

Or as I like to say:

“The secrets of neoliberal capitalist subjects were secrets for the neoliberal capitalist subjects themselves”

Peter Rollins has often also frequently commented on this unreflective religion in a way inspired by his experiences working in Los Angeles. He states that Los Angeles is the religious Mecca of the world today, because its culture is constantly offering new images or mirages of wholeness, completeness and oneness, whether in music, sports, business, or spirituality. He makes the distinction between Belfast and Los Angeles in that, in Belfast, you get high just to get high, but in Los Angeles, you have to get high towards a high purpose of wholeness, completeness and oneness.

However, in general, Rollins’ response to Bown’s query about the necessity of the reflexivity of the Church of the Contradiction, is that while religion continues to operate in a disguised “secret” form in a post-religious secular landscape (e.g. forms of reality tv shows and sports culture), bringing this to reflection is to be able to overcome yet another historical manifestation of the fantasmatic ideology of wholeness. Rollins states:

“Everything is divided and asymmetry is woven into the fabric of everything”

What the Church of the Contradiction is designed to reveal is nothing but the liturgical experience of this self-division, which does not give you a new wholeness, but rather offers a real positive change of subjectivity in the form of a perspectival shift. This perspectival shift should allow for the formation of a subject that can reconcile with not only their everything becoming nothing (whether their religious idea as a Christian, or their religious idea of becoming America’s Next Idol), but also to reconcile with the nothingness in everything (that there is no one who has the answer or the pathway to wholeness).

Thus, the Church of the Contradiction should not literally be another Church, but rather an event space for the deepening of division as positive. I am reminded of a personal reflection on the Absolute in the Preface to Global Brain Singularity which suggested that we “merely have to discern an ethic of repetition that is worthy of its becoming”.2 In other words, to deepen the division as positive we are looking for an ethic of repetition that is itself open to difference and otherness. Thus, we are not looking for an ethic of repetition that can be reified in a single dogma or doctrine, and handed out to all true believers, but are rather looking for an ethic of repetition that is itself dynamic, capable of moving with the real of life, the real of the ins/outs and ups/downs that actually characterise our becoming as a contradiction.

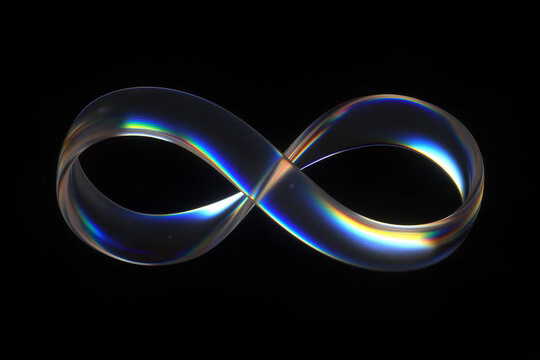

To think this through I think that the geometry of non-orientable surfaces is perhaps our most profound guide. When we think of the structures of non-orientable surfaces, like the Möbius loop or the Klein bottle, we are asked to think in ways that fundamentally disorient our desire for wholeness and oneness. We rather have to think in ways that include within our becoming weird twists and turns, of getting thrown for a loop. We enter an object disoriented ontology.3 In regards to the everything-nothing at stake in the dialectics of religion, we have to be the type of being that can traverse the inside-outside of religion, the profane and the sacred, ideally gracefully.

Can we think of the inside-outside of religion, or the profane-sacred, as itself a strange unity? Can we create with this strange loop?

To be able to think through this question was one of the strange gifts of attending Rollins’ Wake this year, for me. Wake has attracted a strange crowd, and in many ways, a crowd that has walked an opposite path to my own. I will always be on the outside of religion in a sense, because I was not raised in religion. I was raised in a secular household and I think that will always be my default unconscious background. Religion is not my language and history, and when I come to it I spontaneously come with a gaze from the outside. However, most of Wake’s audience comes from the inside of religion, and they now, in various ways, find themselves struggling with the outside of it. The Church of the Contradiction is in many ways to help them exist as in-between subjects.

Outside-in (the church).

Inside-out (the church).

The temptation to avoid in being on the profane outside coming in is that you may find yourself searching for an absolutely sacred inside. You may see the church and think that everything in comparison is a profane hellscape.

The temptation to avoid in being on the absolutely sacred inside coming out is that you may have encountered the self-contradiction of religion as extraordinarily painful, and now think it was all worthless.

But the possibilities in avoiding both temptations are interesting: to become the type of subject that can move in the in-between space, and actually create by being that in-between being. In being the type of being that can exist with the profane outside, you can actually limit it in such a way as to make a new sacred inside. This is the creation of law. And in actually experiencing the limits of the sacred inside, you can appreciate the break and even inspiration that the profane outside has to offer. This is the reconciliation with transgression.

The outside and the inside of religion need each other, in the same way that the sacred and the profane need each other. Creation is possible here, at the level of the unity of law and transgression.

What is interesting, I think, is that if you are living honestly, that is living in the truth of what you are as a life motion, what you find is that the nature of this twisted surface will just reveal itself to you as the truth. That is, if you fully exhaust the inside of sacred space and its law, you will find yourself positing the necessity of profane space as a transgression. If you fully exhaust the outside of profane space in transgression, you will find yourself positing the necessity of sacred space as a new law. In exhausting the extremes, you find yourself in the totality of the looped and twisted disoriented geometry where law and its transgression, as well as transgression of the law, are themselves a weird one.

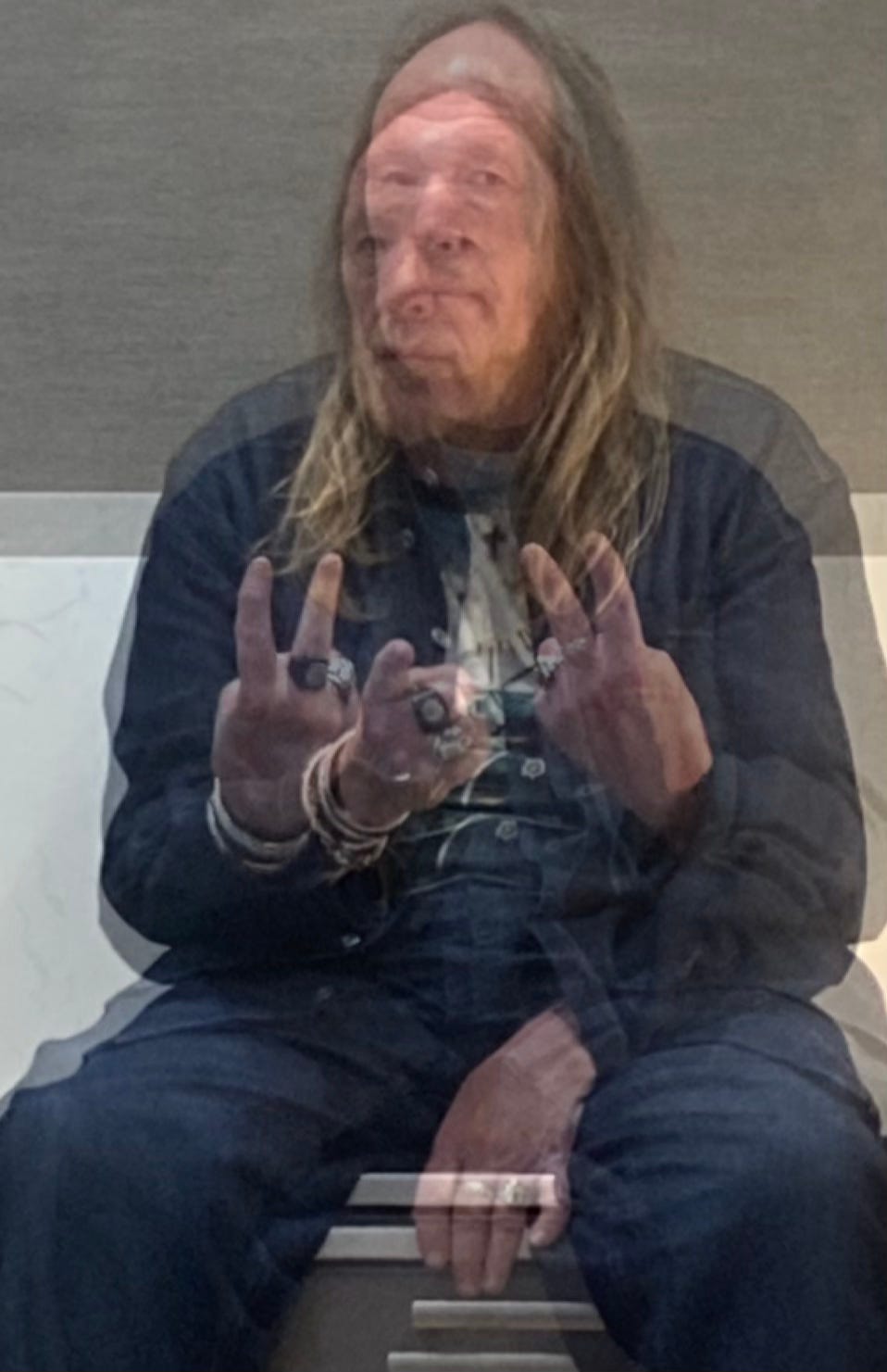

In one of the events at Wake, I had a chance to discuss this at length with radical theologian Barry Taylor. Taylor is a perfect example of this motion because he is someone who has simply lived. He was raised in a non-religious profane space where he encountered the degraded sacred law in the symbolism of the mother and father. In searching for something more he found himself transgressing towards the sacred inside of a music space. However, in living out this space it quickly became the profane world of transgressive sex and drugs, which opened him to a series of experiences that led him into the sacred inside of a lawful Christianity. However, in living out this space, or rather becoming consumed by this space and its law, he realised that he needed to be able to think the profane outside of this inside in-and-with transgressive deconstructive philosophies. Finally, in living out these deconstructive philosophies, he now finds himself as one of the lawful co-leaders of building sacred spaces like Wake with Peter Rollins.4

The point: the totality of living to these extremes reveals the weird twisted loop structure itself, where sacred-profane, law-transgression, are a weird loopy one. I think understanding the totality of this weird twisted loop structure itself is the key to reconciling oneself with the movement of subjectivity, or becoming the type of subject that can work with both sacred-profane, inside-outside of religion.

Furthermore, it is on this level, that I was able to more easily explain why I think direct religious identification or belief means less than people often think, whether we relate to the topic of belief in a religious or a psychoanalytic form. I tend to the idea that what we believe is acted out by a more fundamental unconscious psychic structure, and it is in making this reflexive (the point of the Church of the Contradiction), that allows us to keep moving. In contrast, direct religious belief, I think, is a function of a lack of understanding this weird looped structure of the movement of subjectivity itself. As a result, direct religious belief is always beholden to the other, depends or is being upheld by the other (believing in the same way). However, when you have reconciled with the strange loop of subjectivity, belief is more sustained by the becoming-other itself.

For example, I have always been absolutely turned off by Christian sermons or proselytising, or in general, religious subjectivity that is approaching me in a way that I also need to believe the way they do. In this very motion, I see that they do not really believe in the way that they claim to believe, because their belief depends on a symmetry with me. Instead, what they find is an unbearable asymmetry with the profane outside which they cannot reconcile with, an unbearable asymmetry that is actually and ironically key to their truthful movement and self-creation.

However, and at the same time, the direct belief in atheism can also be expressed in this same way. When someone directly believes in atheism and starts to proselytise their own atheism, and needs other subjects to agree with their form of non-belief, what gets obfuscated here is the place where belief is actually operating in the atheist subjectivity itself. This could be in an extreme form, as in the atheist is actually unconsciously believing as a mirror of the Christian, but it can also appear in ways mentioned above, in sports or music culture.

This is why

has often made the case, as he does in his most recent book Christian Atheism, that Christianity offers a unique experience that opens to an authentic form of atheism. In other words, if one thinks that Christian experience leads to a wholeness and oneness, this is not really Christianity; and if one thinks that one can be atheist without traversing Christianity, this is not really atheism. Funny enough, it is quite easy to make the case that most of the great philosophical thinkers of the last two centuries were Christian Atheists, from Hegel to Marx to Nietzsche to Freud to Lacan. What makes them Christian Atheists is that they all wrestled with the Christian experience and metaphysics, found it lacking in some important way, but also found a new path through this very wrestling match.Its like a historically real and future-oriented incarnation of the word through crucifixion and resurrection. Consider the great radical theologian Thomas Altizer on the idea that thinkers of modern atheism, like Hegel and Nietzsche, could actually be understood as Christian visionaries, a key point in his foundational work The Gospel of Christian Atheism:5

If even a violently hostile passion is a measure of attachment, then who can doubt that a Blake, a Hegel, a Marx, a Dostoevsky, and a Nietzsche were deeply bound to Christianity? Again, each of these prophets was motivated by a profound moral passion -- and despite appearances to the contrary, this is no less true of Hegel -- which, although it assumed an antinomian form, must surely have had its roots in the prophetic traditions of Christianity and the Bible. Indeed, these greatest and most radical creators of modern atheism have ironically proved to be the most seminal influence upon twentieth-century Christian thinking.

To continue, Altizer offers a remarkable suggestion that many of the revolutionary 20th century theologians were actually Nietzscheans:6

Yet it cannot be accidental that so many of the more creative theologians of our century have implicitly if unconsciously shared much of Nietzsche’s vision -- e.g., the early Barth, Bultmann, Tillich, and the late Bonhoeffer -- and it would be difficult to deny the fact that Nietzsche’s whole vision evolved out of what he himself proclaimed to be the death of the Christian God

The interesting paradox to think, for someone deeply wrestling with Christianity, is where to really and truly find the site where speech, the incarnated word, is really alive today? It may not be where we might think. It is likely to be in a surprising place.

Now whether or not I completely agree that the only path to atheism is through Christianity, what I do think, is that one has to dialecticise the transcendental illusion characteristic of religion to really understand and embody a truly visionary atheism. For me personally, this struggle did involve some dimension of, if not Christianity as such, certainly Christian symbolism which overlaps quite nicely with my experience. I would describe it as: in really living out the struggles of my real, Christian symbolism of the trinity is certainly a unique frame, by which I can retroactively make sense of the struggle, as well as situate my current struggle.

Now if we are to extract from Christian Atheism the most general point that Žižek is trying to make in this argument, I would suggest it is some coming to terms with the lack in the big Other, and a recognition that one finds the truth of oneself at the very re-doubled site of this lack as self-division. This interpretation of Christian Atheism, from Žižek to Rollins, tends to focus on the relation between God and Jesus, and specifically the void-point of Jesus’s crucifixion. But what still needs to be developed, in order to stay true with both Žižek’s philosophy and Rollins pyrotheology, is the second moment the negation, that is the relation between Jesus and Holy Spirit.

During Wake, we were treated to an experience to look at two famous paintings by Caravaggio, one that represents Judas’ betrayal of Jesus leading to his crucifixion; and an other that represents a resurrected Jesus surprising his disciples at dinner. What we see here are both negative moments: Jesus separated from God, and Holy Spirit separated from Jesus. This double negation at work in Christian Atheism needs to be affirmed: not only do we need to let go of our desire for wholeness and oneness (God) and experience the lack in the Other (Jesus); but we also need to see this lack in the Other as the very opening towards the condition of possibility for new forms of collectives, or better, new forms of networks.

What I am left with: how do we become key contributors to a network that does not re-solidify or re-cohere into a completed one? How do we move in such a way as that we are the weird ones? How do we establish sites of leadership and direction while also de-centering ourself into sites of other leadership and other directions? How are we to think of that network as the site of salvation itself?

In my experience, not only is it possible, but it is happening. From my first impressions, it is happening in and at sites where the sacred is in touch with the profane, where the law is in touch with its transgression. The type of subjectivity one finds there is the type of subjectivity that is reconciling itself with its own profane transgression of sacred law, or in the type of subjectivity that is reconciling its own sacred law with profane transgression. There is a dance here.

And that brings me to my final point: that what is better than living a life in strict religious identification, and what is better than living a life in unreflexive modern culture, is finding a way to be reflexive of the truth of our life motion today. This may take you weird places, this may result in being spun for a loop. But in the process, you may create something that has never been created before, and open to a truth that needs you just as much as you need it: the living word.

This month at The Portal we will be focused on the metaphysics of self-reference, or self-reference as metaphysics. We will be inviting guests Peter N Limberg of Less Foolish, Greg Dember of What Is Metamodernism?, and Alex Ebert of Bad Guru. To learn more or to get involved, see: The Portal.

Last, C. 2020. Global Brain Singularity: Universal History, Future Evolution, and Humanity’s Dialectical Horizon. Springer. p. xiv.

See: Zupančič, A. 2017. What Is Sex? MIT Press. p. 73-139.

For a detailed exploration of Taylor’s life history, see: Taylor, B. 2020. Sex, God, and Rock 'n' Roll: Catastrophes, Epiphanies, and Sacred Anarchies. Fortress Press.

Altizer, T. 1966. The Gospel of Christian Atheism. The Westminster Press.

Ibid.

Object disoriented ontology where nothing IS at stake 🔥

Julie Reshe’s intersection with Peter here is great. The entanglement/superposition of psychoanalytic cure/incurability—of communion/living deadness.

Nothing to get here;)

I was unable to attend Wake but I look forward to diving into or maybe getting a bit lost in the portal.