Speculative Keys to Contradictory Theopolitics

Trying to Find the Role for Radical Theology in Politics

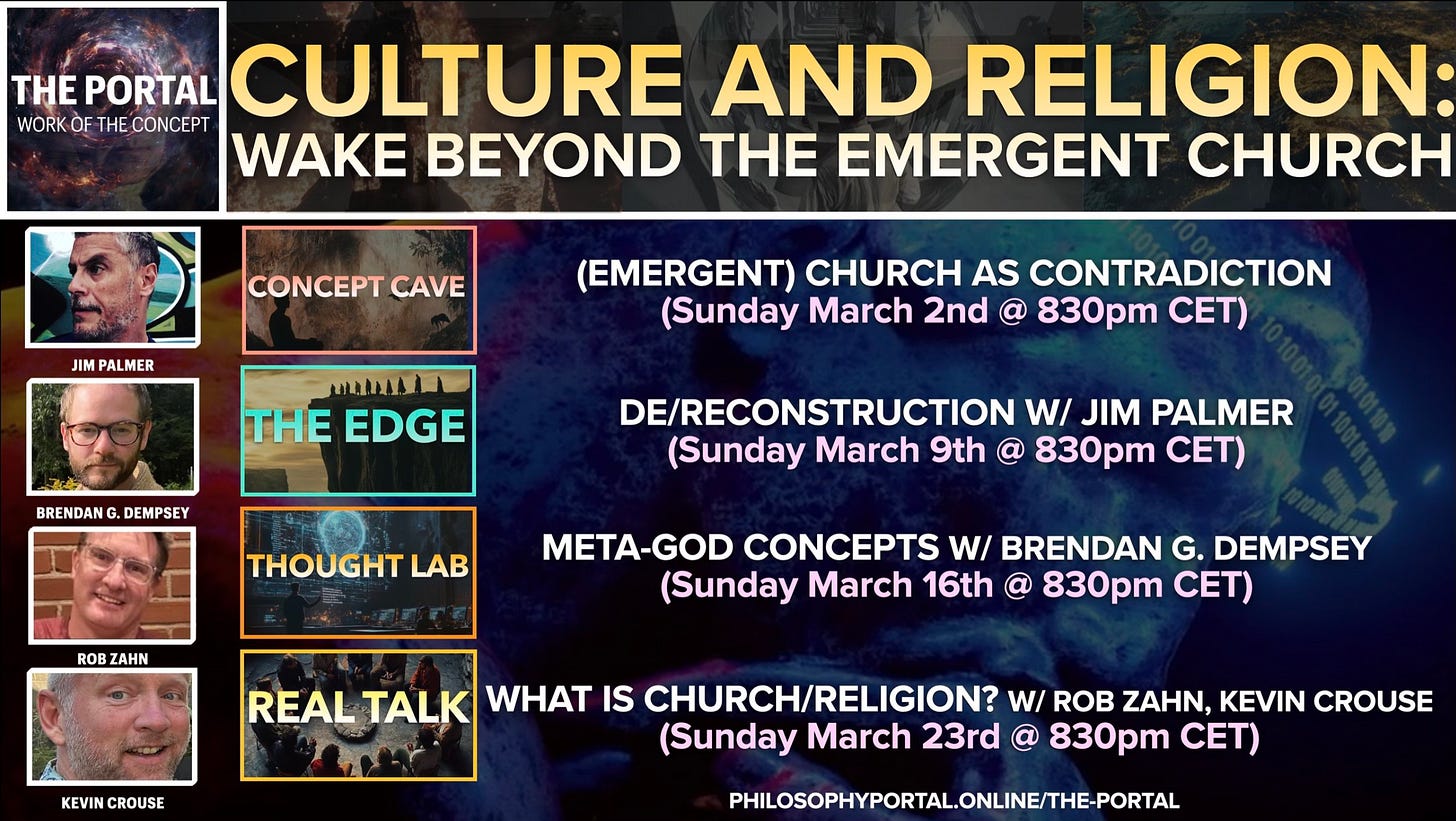

This March in The Portal we will be dedicating a month to the topic of “Culture and Religion” as part of a preparation for Peter Rollins’ “Wake Festival”. In this month we will be attempting to think about religion and church beyond the “Emergent Church” movement with

, , Rob Zahn and Kevin Crouse. To learn more, or to sign up, see: The Portal.This April Philosophy Portal will also be hosting several discussions at Peter Rollins’ “Wake Festival” oriented around and inspired by the Christian Atheism course. Members of the Christian Atheism course get a discount to attend. Otherwise, you can register for the event through Peter Rollins directly. To learn more about the Philosophy Portal side of Wake, see: The Portal at Wake.

Today our culture is experiencing a “religious return”. But the contradiction of this religious return is often totally obfuscated, on both the side of more liberal atheistic politics, as well as on the side of more conservative traditional religiosity.

The liberal atheistic political side will continue to dwell in working out the disorienting contradictions of left-right party politics tarrying with the capital nation-state but disconnected from its underlying theological dimensions. In my opinion, this will inevitably lead to both burn out for the individuals working in this domain, as well as involve repression of the impossible problems of love for both long-term familial and community structure.

The conservative traditional religiosity side will continue to engage culture war battles for the heart of civilisational identity, as if party politics of the capital nation state is completely irrelevant to our contemporary social struggles, or does not play some intensely vital role in our social future. In my opinion, this will inevitably lead to a different form of repression, the repression of impossible problems of secularity and market dynamics which mediate a multipolar global plurality that bring together vastly different ethnic, cultural, and religious groups.

Consequently, and unfortunately, both liberal atheistic politics and conservative traditional religiosity are, conveniently, non-contradictory approaches that continue to feed into the battle for attention in our obscene screen-world.

In contrast to these approaches, what we will try to work towards in this article is the necessity for a contradictory theopolitics that both avoids regression into insular traditional notions of religion unable to think the impossible problems of secularity and market dynamics, as well as demonstrate the importance of a theological dimension for emancipatory political struggle that is able to recognise the dialectics of love for familial and community structure.

The name for the theology which both avoids traditional religion while informing emancipatory politics is radical theology. In my work, I have been most influenced in radical theology in the historical works of Thomas Altizer from the 1960s,1 and in my actual relations, the works of Peter Rollins,2 Barry Taylor3 and Slavoj Žižek.4

These thinkers all offer the “keys” to radical theology:

Altizer offers us the foundation stone of Death of God theology and the term “Christian Atheism” in emphasising that the original heresy of Christianity was linking Christ body to the Church body; consequently, for Altizer, the traditional Christian believes in a dead God captured within a Church structure and turns against life itself, and the secular atheist labours under the delusion that there is nothing radical and emancipatory in the living Christ as the incarnated word

Peter Rollins’ Pyrotheology and Church of Contradiction offer a space for those who have become disenchanted by traditional religion and are looking to live a life in Christ outside of traditional guarantees, which involves embracing lack, doubt, and anxiety (or negative affect in general), or for those who are ready to work with the Church itself as a contradictory site that speaks to the core temptation, and perhaps also core mistake of Christian identity

Barry Taylor’s extension of radical theology involves an embrace of the disruptive fragments, beyond grand narratives or coherent frameworks, as the site of life’s real becoming, as well as the belief that we find the genuinely religious where we would least expect to find it; in short: Taylor’s radical theology is about cultivating a faith in learning to work with disruptive moments and finding God in places that most people associate with secularity or the non-religious

Slavoj Žižek’s radical theology runs throughout his work but has now reached a reflexive maturity in the formal rehabilitation of the term “Christian Atheism”, which posits a dialectical unity between these terms seeking to recognise the central importance of Christian metaphysics as opening the Death of God in the figure of Christ, and paradoxically bringing one to a deeper or truer form of atheism when compared to a straight forward liberal or scientific atheism

Now when we consider these foundational thinkers in regards to the concept of radical theology, as well as its implications for politics, we must first juxtapose their thought against what most people will think when it comes to traditional religion. In relating to traditional religion, we are basically dealing with the following structure:

Organisations preaching the “Good News” that Christ is God, that He died on the cross for your sins, and that only He can satisfy and save your soul for both the good life, vibrant family and community, as well as the afterlife

Organisations emphasising that faith is related to belief in an omnipotent God who upholds the distinction between sacred and secular (or profane), and who functions as a “Father object” that we love, pray to, confess our sins, orient our life

Organisations community work oriented/orbiting the mission of changing minds with theological answers to build society under a religious structure of unified belief of a really existing substantial Other (God) who favours his own people

Here I will use the work of Peter Rollins’, and specifically his pyrotheological notion of the “Church of Contradiction”, to respond to these structures of traditional religion:

Organisations preaching “Good News” that one can only be saved in the difficulty of life where we don’t know the secret to an all-inclusive community existence because living in Christ is living in relation to real otherness (enemy/neighbour)

Organisations emphasising faith is unrelated to direct belief in God but rather found in living the real of life’s contradictions without guarantee, a disorienting process where the sacred can become profane, and the profane can become sacred

Organisations community work opening the possibility for communion around a shared lack embracing uncertainty and unknowing, the most real dimension of Christ’s death reveals we must tarry with negativity of existence

First off, when it comes to civilisation as a project, I would suspect that traditional religion is always going to get more attention than radical theology. In this sense, radical theology is not “for everyone”. Traditional religion, in all of its various forms, is going to provide basically what the ego wants, and when it comes to the most disenfranchised and vulnerable populations, what the ego needs in difficult times, and for what is often an unbearably difficult life. Traditional religion seeks to provide security, safety, and comfort against the vicissitudes of life, and the painful heartbreak that is inherent to human existence. In Marx’s words, it is an “opium” with a real rationale, the “heart” of a “heartless world”, the “soul” of “soulless conditions”.5

However, Marx may also suggest that traditional religion, while comforting in a heartless world and in soulless conditions, it is also a way for self-consciousness to avoid itself, or to lose itself.6 For those who are interested in more directly confronting the heartlessness and soullessness of our world without a transcendental guarantee (in a unified community, of an eternal afterlife for your soul, or an immanent eschaton), radical theology becomes absolutely essential. To frame radical theology in Altizerian terms: radical theology is there when either, on the Christian side, the transcendental illusion that traditional religious structures offer fails; or on the Atheist side, when the mystery of Christ appears as a real materialist question for one’s own existence. Here in Altizer’s own words:7

“The honest Christian must admit that the God he worships exists only in the past -- or he must bet upon the gospel, or "good news," of the God who willed his own death to enter more completely into the world of his creation. And the honest atheist, who lives forlornly bereft of faith, will want to understand this revolutionary and definitive statement about a Christ who is totally present and alive in our midst today, embodied now in every human face.”

Now that we have outlined the basic differences between radical theology and its relation to traditional religion, we need to more explicitly address how radical theology relates to atheist politics. Žižek opens his latest work Christian Atheism, with the following claim:8

“Political theology necessarily underpins radical emancipatory politics”

In order to get at this dimension, we can note that, for radical theology, the structures of traditional religion can appear, not only in an explicit religious form, but also in secular materialist forms. In other words, often times, those growing up without religion, or those leaving religion, can find themselves enacting an ideology in political activism, that gives one the impression of a traditional religious form as described above. In such situations, one’s politics becomes one’s unconscious religiosity, either in terms of attempting to save humanity’s soul from an evil otherness, or proposing political programs that are designed for worship as the true path to salvation, or as a political community that works under a unified belief structure. Whether explicitly expressions that mirror the forms of traditional religion or not, these often implicit forms of political activism represent the way our unconscious still acts out a religious process in a culture that explicitly purports to be secular and atheist. Moreover, these implicit forms of political activism have deceptively taken many shapes, whether in Marxist forms in communist states, or in liberal forms in neoliberal nation states.

However, radical theology is also important when confronting a form of political activism that is purely liberal and atheistic in its orientation, meaning a form of political activism that cannot overcome itself within the capitalist nation state towards a socialist project. In this context, I think the proper dialectical stance for a radical theologian experimenting with the concept of Christian Atheism in practice, is to not only inject atheism into traditional religious circles, but also to inject a radical Christ into conventionally atheist circles. While this “injection of atheism” into “traditional religious circles” involves a strategic and contextual deflating of the potentially destructive illusory clinging to a transcendental guarantee, we could say that an “injection of a radical Christ” into “conventional atheist circles” involves a strategic and contextual emphasis on an ethics that disrupts a liberal hedonistic apathy towards self-overcoming.

Paradoxically, the point of injecting atheism into traditional religious circles, as well as injecting a form of Christ into atheist political circles is identical: to reveal the actual function of a Christ-like disposition that opens one unto the living dynamics of Holy Spirit. Here Holy Spirit, following Altizer, is not necessarily within the Church, and also not necessarily within a political party structure (although it does not exclude those domains). What is essential about Holy Spirit, for Christian Atheism, is that it exists without either transcendental guarantee (a form of the big Other), or a liberal clinging to ego or the self (a refusal to “carry the cross”). The Holy Spirit, we might suggest, is a result of both processing the “death of the big Other” (God) as a necessary transcendental illusion in a heartless/soulless world, and a willingness to pick up the metaphorical cross in one’s own work towards the beyond of oneself.

The hypothesis of radical theology is that what can result from this “double negation” is Holy Spirit.

Thus, in both circumstances, radical theology is designed to open the subject up to the unknown real of human failure as giving insight into the nature of reality itself. In this opening, Rollins’ specific approach as a radical theologian is three-fold:

Teaching in parables: the radical theologian teaches using the form of joke structure, narratives and counter-narratives that spin you on your head in counter-intuitive ways, offering stories that make you feel like a child pregnant with possibilities growing beyond what you expected or anticipated

The Self-Divided God: the radical theologian emphasises the uniqueness of Christianity in, not the all-knowing/powerful God guaranteeing your soul in the afterlife, but rather the God divided from Himself, the God of the cross and crucifixion that both does not know his Father, and feels abandoned by his Father

Hegelian Reformation: the radical theologian recognises Hegelian philosophy as equivalent to previous theological revolutions (e.g. Luther, Aquinas, Paul), where Christian life is reinvented through modern philosophy, overcoming a dualistic ontology for subjective capacities necessary for embracing living contradiction

However, Rollins’ pyrotheology as a whole also embraces other key elements, inspired by both Girardian anthropology and Lacanian psychoanalysis. Both of these elements are designed ultimately to provide the subject with the tools necessary to confront a more disturbing social reality than traditional religion may be willing to confront:

Girardian Anthropology: our desire is the desire of the other, leading to irreducible rivalry and scapegoating dynamics that need to be worked out through a deep internalisation of the meaning of Christ’s story/life/existence

Lacanian psychoanalysis: the truth is that no one knows what they want which necessarily leads us to a confrontation with anxiety itself, where anxiety becomes the only emotion/affect that does not lie, but give one true self-insight

Social Real: radical theology opens us to the uncanny jouissance in the other; the impossible demand to live in the hurricane of the other, which requires other-worldly powerlessness and weakness, the capacity to bless those who curse us, repay evil with kindness, and to love those who hate you

What can we expect when we think through all of this? For Rollins’, we do not collapse back into ‘yet another Protestant denomination’, but rather come to, perhaps, the truth of Protestantisms’ denominational spitting itself in the idea of a “drive denomination”. The “drive denomination” is simply the recognition that difficult splits and ruptures, and not coherent unities, are the truth of our spiritual process in the world. This is why, for radical theology, Christianity centres a “split-God”.

In this context, Rollins’ invites us to reflect on the “Theology of the Not-One”, which, at its core, emphasises the universality of division, and the atheism at the heart of Christianity itself. However, it also extends as a metaphysics with applications representing truths in many different fields:

Modern democratic politics: the not-One of society itself opens us to the multiplicity of representative democracy (and away from the One-All of monarchy)

Modern mathematical logic: the not-One of every mathematical theorem, that there is no internally self-consistent system of axioms

Modern Darwinian biology: the not-One of every organism found in the truths of natural selection that organisms do not correspond to perfect unified form

Modern quantum physics: the not-One of wave-particle duality in the fact that reality is indeterminate (wave) in regards to its own identity (particle)

Modern psychoanalytic clinic: the not-One of the subject in the real of the self-division between consciousness and unconscious aspects of our mind

Rollins’ radical theology should also be juxtaposed against two different variants of “Cultural Christianity”: the Dawkins form and the Peterson form:

the Dawkins form of “Cultural Christianity” attempts to emphasise the importance of modern liberal social morality without the need for an absolute or a supernatural dimension; and

the Peterson form of “Cultural Christianity” emphasises a social morality with support from traditional myths of the absolute or a supernatural dimension (their “psychological significance”).

In contrast to both approaches, Rollins’ pyrotheology suggests that neither form is “atheist enough”. The first Dawkins’ approach offers a straight forward non-dialectical atheism where God cannot die because God never existed. This approach leaves us with a liberal social morality which can neither explain its own historical appearance (as the result of the working through of the Death of God itself), as well as leaves us with the inability to struggle beyond liberal social morality (in and through the ethics of Christ). The second Petersonian approach also offers a non-dialectical approach in centring a reified Christianity where God exists in our myths and stories. This approach could in principle lead to an illiberal interpretation in centring a revolutionary politics in an ahistorical return of Orthodox Christianity (where the truth of the body of Christ is held as the “one true church”).

While Dawkins does not explicitly state that his politics reifies liberal social morality; and while Peterson does not explicitly state that his politics reifies an ahistorical Christianity; the consequences of their projects lead in this direction: with Dawkins, there is no real thinking through of a socialist politics, and with Peterson, there is an active rejection of a thinking through socialist politics. In contrast, radical theology opens up the potential to bring in the legitimacy of the Christian dimension as potentially necessarily underpinning an emancipatory tradition that points towards both the conditions of possibility for liberal social morality, as well as its self-overcoming in a socialist politics. For radical theology, God existed as a substantial Other, died as a specific singular human being, and through this death becomes the inexistent thing which insists through our collective praxis. In this way, God as an inexistent thing reveals to us the persistent abyssal nature of, on the epistemological level, the “community of belief”, and on the ontological level (potentially), “quantum wave oscillations”.

Now, to iterate, this is not to say that radical theology can become the dominant or primary theological scaffolding of civilisation, nor does it need to. What this article is arguing is for the importance of radical theology, specifically for those who are finding themselves encountering the unreflexive contradiction of conservative traditional religiosity, or the unreflexive contradiction of liberal atheist politics, and looking for some way to affirm a contradictory theopolitics that can transgress traditional religion as well as uphold an emancipatory foundation for contemporary political struggles. Insofar as radical theology proposes to situate itself within a civilisational project, it is in and through a radical psychoanalytic reading of religion as it relates to the modes of demand, desire, and drive. Here we are going to think about religion as “demand” and “desire”, and finally, the possibility of a “religionless Christianity” in a “drive denomination” through processing the contradictions of religion qua unified transcendental illusion as both expresses in modes of “demand” and “desire”. First:

Demand religion (1) relates to the infantile satisfaction of immediate needs (food, rest, socio-sexual support/gratification); and potentially correlates to a “healthy narcissism” in meeting given “auto-erotic” repetitions

Desire religion (2) relates to childhood/young teenage development in craving for what is perceived as a lost object in frustrated processing of the necessity of work; and potentially correlates to Oedipal struggles with the lack in the parental Other

Drive religionless (3) is equal to the adult drive to enjoy the negative/impossible itself in the Christ-form of sacrifice/lack as the real thing/process itself; and potentially correlates to capacity to exist beyond traditional religious structures

Consequently, when radical theology is thinking about religion as both a historical and civilisational phenomena, we are thinking about processing a transcendental illusion that mirrors the repetition of demand and desire in every new human being, as well as the necessity of overcoming that transcendental illusion in the mode of the drive. This overall path correlates to a reconciliation with an antagonistic ground of being, with God itself as not-One with itself (which is the condition of possibility for thinking the dialectics of the trinity).

Here God beyond traditional religion or formal church structures can be thought of in terms of the Holy Spirit itself: the embrace of lack opens one to God as an excessive object beyond categories or structures. In this way of thinking, God is not so much an experience but rather a non-experience internal to experience, a short-circuit of experience, inherently confusing and disorienting, painful even. In Hegelian terms, we could think of this as becoming of Holy Spirit in the unity of “being-nothing”, which is why Rollins’ has articulated a radical theology where the role of “nothing” takes a special primacy in its unity with being. He suggests the following: 9

Nothing Lives, Binds, and Saves

Within the context of contemporary liberal secular culture which struggles with “nothing” qua “nihilism”:10

Nothing Lives: either everything is dead, or the nothing itself lives

Nothing Binds: we are all separate individuals, or the nothing itself binds

Nothing Saves: we are all doomed, or the nothing itself saves

In other words, we can interpret our present moment in liberal secular culture in a straightforward non-dialectical way, where nothingness is interpreted in its standard nihilistic form (after the Death of God we are all isolated atoms doomed to nothingness); or we can interpret our present moment in liberal secular culture in a paradoxical dialectical form, where nothingness is actually the opportunity for a more real becoming than we find in traditional religious communities.

However, this opportunity requires cultivating a contradictory theopolitics. For Rollins, as for Žižek, this requires sublating a theology that is capable of struggling with figures like Kant, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Freud, Lacan, Girard, and others. Rollins notes that, while these thinkers are known for their difficulty, even their impenetrability or dangerousness, this very difficulty and danger is part of the message. In other words, one cannot just ask ChatGPT for descriptions of these thinkers works, or read Wikipedia entires about them, one has to tarry directly with their texts in an arduous labour, not dissimilar to how real theologians struggle with the Bible. This is all part of the radical theological work. The work itself is to turn frustration (of misunderstanding) into enjoyment.

When one is reading for a straight forward understanding, one is once again repeating the structures of the universality of the Father, in the way that a Dawkins’ form of Cultural Christianity operates under the “scientific Father”; or the Petersonian form of Cultural Christianity operates under the “mythological Father”. The point of struggling with the aforementioned thinkers, is not to reintroduce a new universal Father, but rather to introduce the foundation for the future of theology in the form of reconciling with subjective excess, the subject as (uncategorisable, unstructurable) exception (to any category, structure).

On the level of theology, what one is brought to in this work is the key to one’s own subjectivity in the painful experience of exclusion: of not being integrated into a communal totality or whole guaranteeing your soul’s safety and security for eternity. The key to radical theology is a reconciliation with that pain of being excluded because in reconciliation with this pain, one is capable of a true becoming (being-nothing). In regards to the aforementioned structure of the demand-desire religion to the potential drive in religionless Christianity, is that we have the condition of possibility for turning both primal impotence (our dependence on the Other and our enslavement to automatic repetitions), as well as childhood trauma (the primordial loss of the object), into a triumph (the joy of the drive).

Rollins’ has noted to me personally before, that in beautiful individuals, he always thanks God for what he interprets as their condition of possibility for having becoming beautiful: the transformation of trauma, turning a loss into a triumph.

On a final note: the Church of Contradiction, again following Altizer, recognises that Christ’s Body cannot be linked to the Church as traditionally understood. The wager of Christian Atheism, I hypothesise, is that Christ’s Body is not in the Church but in the broken impotent body itself. From a psychoanalytic perspective: the catastrophe has already happened in birth itself, and the repetition of the primal scene which orients analysis is the core of one’s being excluded (from parental copulation as a stand-in image of drive-joy). No Church can reverse this, no Church can include what has already been excluded in the recreation of the primal scene. And while the Church may be historically necessary as a transcendental illusion of a reconstituted social body, for Rollins’ Church of Contradiction, we focus on the “liturgy of lack”, that which symbolises the trauma of being a constitutive outsider in relation to both conservatism of traditional religion and liberalism of atheist politics. But in cultivating the form of subjectivity that can work with this constitutive “outsideness”, what I articulated earlier as the dialectical practice of injecting atheism into traditional religious circles, and injecting Christianity into atheistic political circles, there is a higher order theopolitics possible, a theopolitics that works with the contradiction as such.

This March in The Portal we will be dedicating a month to the topic of “Culture and Religion” as part of a preparation for Peter Rollins’ “Wake Festival”. In this month we will be attempting to think about religion and church beyond the “Emergent Church” movement with

, , Rob Zahn and Kevin Crouse. To learn more, or to sign up, see: The Portal.This April Philosophy Portal will also be hosting several discussions at Peter Rollins’ “Wake Festival” oriented around and inspired by the Christian Atheism course. Members of the Christian Atheism course get a discount to attend. Otherwise, you can register for the event through Peter Rollins directly. To learn more about the Philosophy Portal side of Wake, see: The Portal at Wake.

If you enjoyed this article, check these videos:

Altizer, T. 1966. The Gospel of Christian Atheism. Westminster Press.

Rollins, P. 2024. The Profane Temple. Everyday Analysis.

Taylor, B. 2020. Sex, God, & Rock ‘N’ Roll: Catastrophes, Epiphanies, and Sacred Anarchies. Fortress Press.

Žižek, S. 2024. Christian Atheism: How to be a Real Materialist. Bloomsbury.

Marx, K. 1970. Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. Oxford University Press.

Ibid.

Altizer, T. 1966. The Gospel of Christian Atheism. Westminster Press.

Žižek, S. 2024. Christian Atheism: How to be a Real Materialist. Bloomsbury. p. 1.

Rollins, P. 2024. The Profane Temple. Everyday Analysis.

Ibid.