Technological Singularity as Idea

Preview of/preparation for the first class with Michael Downs "Land, Žižek, and Singularity" course

This October in The Portal we will be hosting underground theorist Michael Downs of

and author of Capital vs. Subjectivity for a month dedicated to the ideas he has been developing related to “fault line theory” between Nick Land and the CCRU, and Slavoj Žižek and the Ljubljana School, and as this theory relates to the idea of technological singularity. To get involved, check the link below:The origin of “technological Singularity” as an idea is traditionally attributed to computer scientist I.J. Good, whose prophetic concept of an “intelligence explosion” was derived from speculative reflection on mid-20th century computer systems. In 1965, Good combined his knowledge of computer science with theoretical insight from the burgeoning field of cybernetics, to suggest that future computer agents could catalyse the growth of positive feedback loops opening successive self-improvement cycles.1 If one lets their imagination run with this idea, one can quickly find oneself with the idea of a powerful superintelligence that, not only no longer needs humans for its recursive improvement, but far surpasses human intelligence and starts to modify its own source code. Here is a direct quote from Good:2

“Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion’, and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.”

The actual term “technological singularity” was formally introduced a few decades later by computer scientist turned science fiction writer, Vernor Vinge, who wrote a technical paper in 1993 titled “The Coming Technological Singularity”. In my opinion, this paper holds the record for the most grandiose, dramatic, and to-the-point abstract of all time:3

Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended.

Is such progress avoidable? If not to be avoided, can events be guided so that we may survive? These questions are investigated. Some possible answers (and some further dangers) are presented.

Now in 2025, we can say Vinge’s prediction of superhuman intelligence by 2023 was off. However, considering the dominance of artificial intelligence in our society, he was not only pointing vaguely in the right direction, but had isolated the concept “technological singularity” that would provide the metaphorical inspiration for the next generation of computer scientists to work out the consequences of the rapid acceleration of computation capacity. The metaphor of “technological singularity” was so powerful because it could be connected to more rigorously developed concepts in maths and physics. For example, by 2005, inventor and tech entrepreneur Ray Kurzweil released his now classic book, The Singularity Is Near, in which he explicitly framed developments in computation using this link:4

“To put the concept of Singularity into further perspective, let’s explore the history of the word itself. “Singularity” is an English word meaning a unique event with, well, singular implications. The word was adopted by mathematicians to denote a value that transcends any finite limitation, such as the explosion of magnitude that results when dividing a constant by a number that gets closer and closer to zero. Consider, for example, the simple function y = l/x. As the value of x approaches zero, the value of the function (y) explodes to larger and larger values.

Such a mathematical function never actually achieves an infinite value, since dividing by zero is mathematically “undefined” (impossible to calculate). But the value of y exceeds any possible finite limit (approaches infinity) as the divisor x approaches zero.

The next field to adopt the word was astrophysics. If a massive star undergoes a supernova explosion, its remnant eventually collapses to the point of apparently zero volume and infinite density, and a “singularity” is created at its center. Because light was thought to be unable to escape the star after it reached this infinite density,16 it was called a black hole. It constitutes a rupture in the fabric of space and time.

One theory speculates that the universe itself began with such a Singularity. Interestingly, however, the event horizon (surface) of a black hole is of J finite size, and gravitational force is only theoretically infinite at the zero-size center of the black hole. At any location that could actually be measured, the forces are finite, although extremely large.

Kurzweil continues to develop the connection, with explicit reference to both Good and Vinge, as follows:5

From my perspective, the Singularity has many faces. It represents the nearly vertical phase of exponential growth that occurs when the rate is so extreme that technology appears to be expanding at infinite speed. Of course, from a mathematical perspective, there is no discontinuity, no rupture, and the growth rates remain finite, although extraordinarily large. But from our currently limited framework, this imminent event appears to be an acute and abrupt break in the continuity of progress.

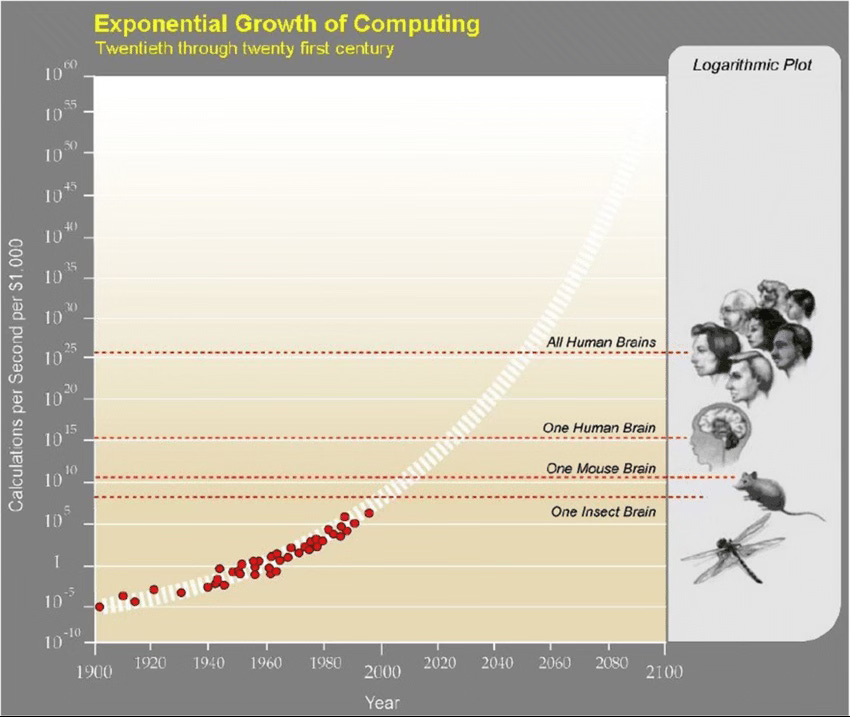

The key to Kurzweil’s contributions to the technological singularity literature is his emphasis on the “exponential” nature of computational growth (as opposed to linear), which leads to much faster changes than we would intuitively expect (which he uses to describe the way most people have been blind-sided by the developments in computer power in the past decades). In The Singularity Is Near Kurzweil develops several models demonstrating the exponential nature of change in computation, and also extrapolates these models into the near future to make specific predictions about what technological powers we can expect to exist with in the 21st century. His most famous and important predictions related to the idea of technological singularity involve computers that can match human-level language capacities by 2029, and human collective intelligence by 2045.

Since 2005, the idea of “technological singularity” has gained widespread popular appeal, not only becoming closely linked and associated with the rise and use of artificial intelligence agents in our society, but also drawing attention of the world’s most famous scientists and entrepreneurs. The most common representations of technological singularity have been in the form of framing it as an “existential threat”; for example, popular scientist Stephen Hawking claimed “the development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race”;6 and entrepreneur Elon Musk claiming artificial intelligence is “the greatest risk we face as a civilization”.7 Even those within the fields of artificial intelligence, like computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton — often referred to as the “God-Father of AI” — now believes that there is a 10-20% chance that AI will lead to human extinction in the next three decades.8

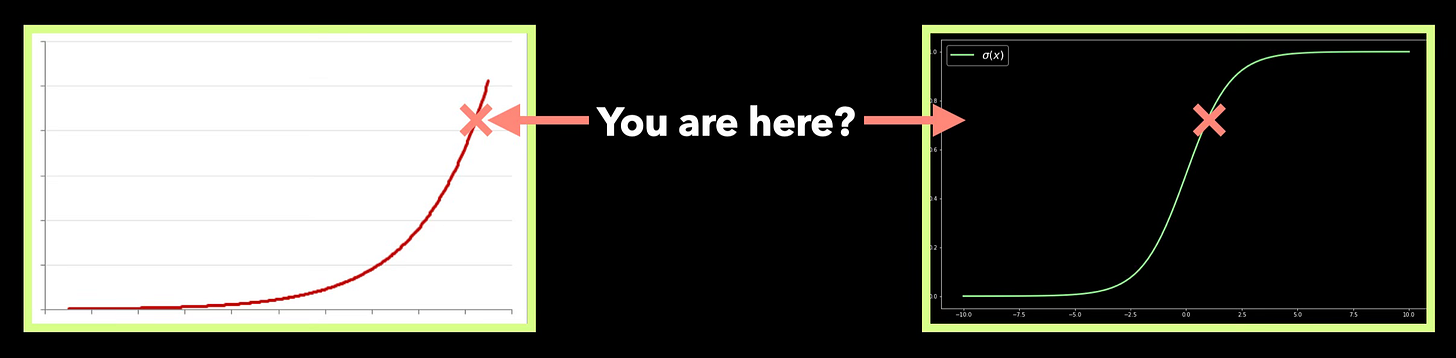

These are sensational claims, but they are supported by convincing data derived from exponential growth of computational power in the past few decades, and mythologised with reference to aforementioned figures like Good, Vinge, and Kurzweil. And at the same time, it must be emphasised that there are opposing sentiments that receive less popular attention. Indeed, a sizeable minority of scientists and technologists suggest that the speculation about AI as an existential threat is baseless fear-mongering because humans cannot be exhausted by the category of “intelligence” (whether natural or artificial), and also because the presupposition that exponential growth can continue without end, is simply wrong. For these scientists and technologists, we should pay attention to the distinction between intelligence and spirit, or intelligence and wisdom, as well as pay attention to the possibility that what is referred to as exponential growth, is in fact just the sharp incline curve of a sigmoidal growth pattern, which is more likely to reach a stable plateau, than to reach an “infinite” post-human singularity.

These concerns were front and center for me in the writing of my doctoral thesis, Global Brain Singularity, which grows out of a related but distinct form of thought more concerned with human nature and spirituality as a whole (as opposed to reduction to intelligence), and the possibility of sigmoidal growth curves as “metasystems” (as opposed to strict interpretations of exponential growth to infinity).9 In Global Brain Singularity I try to provide a richer context to the idea of technological singularity than the one we find among the technologists who have traditionally had the most to say about it. I think the potential within the present moment of technological singularity from the perspective of “universal history”, “future evolution” as well as a “dialectical horizon”. This work is certainly inspired by thinkers like Kurzweil, but at the same time, it strives to be more critical in its interpretive motivations (as opposed to equating biological transcendence to a type of deified determinism), and it strives to be more general in its vision and scope (as opposed to reductive to technological exponents). The four sections of the work can be summarised as follows:

Part I: Contextualising Our Present = thinking the present moment of cultural and technological dynamics in the context of cosmic evolutionary history allows us to frame contemporary acceleration of technology/erosion of traditional culture as a remarkable anomaly in spacetime.10

Part II: Challenges of a Global Metasystem = thinking the present moment as a meta-systemic whole requires thinking change not just in terms of culture and technology, but also in terms of political-economy, where we can potentially learn how previous metasystem transitions changed political and economic realities.11

Part III: Signs of a New Evolution = thinking about the possible future of evolution in the context of evolution as a physical, chemical, biological, cultural, and technological process allow us to make predictions and test speculations beyond a reductive evolutionary perspective.12

Part IV: Field of Twenty-First Century Knowledge = reflecting contemporary knowledge using dialectical method is necessary for constructing on the pathway of technological singularity so that we avoid projecting on the future that is impossible to predict and stay with thinking the present moment.13

In short, this approach emphasises the following:

Recognition that we are living through a time period of unprecedented historical change (limiting our capacity to make predictions about what we are undergoing, not only because we are part of the process, but also because what we are a part of is itself a historical anomaly given current knowledge).

Recognition that previous metasystem changes have resulted in fundamentally different political and economic structures and realities that would have been difficult or impossible for historical human beings to cognise, and that much of our contemporary political-economic reality is in turmoil because of this fact.

Recognition that evolution is a much more general phenomenon than we have traditionally conceived from a biological point of view, and that a radical extension of the evolutionary paradigm forces us to consider speculative possibilities that may de-center the human experience and the human body.

Recognition that the importance of philosophy and dialectics is in need of being reclaimed because it is this approach to knowing which may allow us to cultivate wisdom in relationship to the actual singularity of our present moment, which cannot be navigated with reference to previously acquired knowledge.

Throughout our first event in The Portal this month, focused on technological singularity with Michael Downs, we will use a philosophically informed approach to assess the technological singularity “as idea”, that is to think the constellation of propositions that have been forwarded over the past half-century to gain a comprehensive understanding of how to think with this concept. Here we will try to reflect the following categories or dimensions of technological singularity:

Theopolitics

Norbert Wiener’s God and Golem (1963): cybernetics is creating machines with theological implications (man as creator of gods or beings with god-like properties), and this in turn generates enormous ethical problems for politics14

Hugo de Garis’s The Artilect War (2005): global politics in the 21st century will be dominated by the “species dominance” issue, of whether we should build post-human technological gods that will sideline human beings in evolutionary terms15

Zoltan Istvan’s The Transhumanist Wager (2013): ethics of the political fight this century will be for a transhumanist revolution shifting religious ethics of the after-life to indefinite life extension on earth via science and technology16

Humanism

Julian Huxley’s Transhumanism (1951): argued that the concept of humanism needs to be extend towards the evolutionary transcendence of the human using science and technology, as opposed to a romantic reification of the human being17

Francis Fukuyama’s Our Posthuman Future (2002): proposed that the development of transhumanist technology (artificial intelligence, genetics, robotics) poses an immediate threat to both the human species and our liberal democracies18

James Hughes Citizen Cyborg (2004): Liberal democracies must learn to work with a constructive concept of transhumanism in order to navigate the sociopolitical challenges that will be faced in the near-term future of global governance19

Economy

Jeremy Rifkin’s The Zero Marginal Cost Society (2014): the emerging technological revolution will bring marginal cost of producing both goods and services to near zero, forcing an eclipse of capitalism and the rise of a collaborative commons20

Peter Diamandis’ Abundance (2012): contemporary technology makes possible a future in which all humans have free abundant access to everything necessary for a standard of living that far surpasses the standard of living of historical society21

Martin Ford’s Rise of the Robots (2015): technological acceleration is making most human jobs obsolete, whether blue collar or white collar jobs, whether lower or middle class jobs, we are likely to live through a large-scale automation22

Post-Biology

Hans Moravec’s Mind Children (1988): we are approaching an age in which the boundaries between biological and post-biological intelligence dissolves, where biological humans become cyborgs, and technological intelligence emerges23

Vernor Vinge’s The Coming Technological Singularity (1993): we are approaching an event comparable to the rise of life on Earth in the form of technological life-forms that are created by, but no longer dependent on, human beings24

James Barrat’s Our Final Invention (2013): developing the notion of I.J. Good, he suggests artificial general intelligence could become super-intelligent through recursive self-improvement, leading to existential risks for biological humans25

Global Brain

Kevin Kelly’s What Technology Wants (2010): focuses on the concept of the “technium” as not only a massively interconnected system of technology, but as a desiring force in continuity with biology, but with its own emergent teleology26

Ben Goertzel’s Creating Internet Intelligence (2002): we cannot understand singularity from perspective of AI but as global computing networks developing an autonomous intelligence that will use human scientists to shape its evolution27

Francis Heylighen’s Return to Eden? (2014): the global brain as the collective network pattern of humans and machines has the potential to embody traditional notions of God’s omni-properties: science, presence, benevolence, potence28

Techno-Speculations

Max Tegmark’s Life 3.0 (2017): explores social scenarios in which artificial general intelligence far exceeds human intelligence, bringing us towards realities that range from abundant political utopias to theo-apocalyptic end-times29

Michio Kaku’s The Future of Mind (2014): discusses possibilities of advanced technology to alter the mind, making possible realities previously only found in science fiction: telepathy, telekinesis, artificial intelligence and post-humans30

Eric Drexler’s Radical Abundance (2013): argues that scientific progress in nano-technology (specifically: atomic manufacturing) will soon have the power to produce total abundance at scale for no or low cost31

Throughout the first session, we will also discuss, compare and contrast, the two leading contemporary technologists regarding their underlying philosophies, as well as the possibilities and ethical dimensions of technological singularity:

Ray Kurzweil’s The Singularity Is Near

The Six Epochs (cosmic evolutionary teleology): (1) Physics and Chemistry, (2) Biology and DNA, (3) Brains, (4) Technology, (5) Merging Technology and Human Intelligence, (6) The Universe Wakes Up (infusing matter with mind)

Intuitive Linear vs. Historical Exponential View: we assume a gradual step by step process of change but technological progress is exponential meaning that there is an acceleration of doubling times (e.g. price performance of computation)

“Singularity”: maths = value that transcends finite limitation and approaches infinity; physics = star undergoing supernova collapses to point of zero volume (0) and infinite density (∞); technological = vertical phase of exponential growth that will appear to be expanding at infinite speed for humans32

Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence

History teaches us that evolution unfolds with distinct growth modes, each more rapid than the previous, suggesting that our future may be characterised by the emergence of a new distinct growth mode that will appear “infinite” (singularity) from our current point of view

Humans are currently superior to machines in terms of general intelligence, but artificial intelligence, whole brain equation, human-machine interface, and computer networks are all shaping a new evolutionary process that is likely to subordinate human general intelligence to artificial general intelligence and possibly even superintelligence

Superintelligence can take the form of speed (faster), collective (group), and quality (transcendent), and all three forms have a vastly higher potential to manifest on a machine subtract as opposed to a biological substrate33

And finally, we will zero-in on the “philosophical fault-line” that Michael Downs is developing regarding the philosophy of Nick Land and Slavoj Žižek on the topic of technological singularity. For Downs, the focus on Land starts with Land’s attack on Neo-Marxist Leftist politics that it has become “transcendental miserablist” in regards to capitalist realism; and the focus on Žižek as a response to technological singularity that emphasises seeing the positive in the negative as opposed to closing the gap with technological devices (brain-computer interface):

Nick Land, Transcendental Miserablism

Neo-Marxists replaced belief in economic transformation with cosmic despair about the realities of life in capitalism, e.g. Fisher’s capitalist realism has “swallowed the future” (we live in a post-future world)

The Left is now “transcendental miserbalist”: pessimistic, depressive framing of reality through which it views all experience (e.g. embodied in Frankfurt School, i.e. capitalism as unbeatable and existentially devastating)

Libidinal Materialism: rejects human-centric point of view, celebrates impersonal inhuman forces of the Outside; values death, excess and feral materialism over subjectivity and meaning (human-centric, human-sentimentalities)

Capitalism as Outside (Fanged Noumena): capitalism is not just an economic system, but a self-replicating alien force driving technology beyond human control to the point of post-human reality (M-C-M’ = outlives all humans, mechanism for machine self-replication)34

Slavoj Žižek, Hegel in a Wired Brain

The idea of a wired brain (brain-computer interface) fundamentally changes the human condition by cutting out linguistic mediation between brains directly connecting brain to brain via machine interface (equal to a collective immersion in “Singularity”)

Soviet Communists: “bio-cosmist” view of overcoming the human being with socialist science and technology capable of materially realising the goals of religion (e.g. collective paradise, overcoming suffering, full immortality, resurrection of the dead, conquest of space and time)

The Fall that Makes Us Like God: gap/lack as cause of desire is the mark of The Fall (from Eden, separation from paradise) which techno-gnostics want to close with brain-computer interface (“overcoming alienation”); but collective immersion in Singularity is apocalypse/question: what kind of apocalypse?35

Michael Downs, Capital vs. Subjectivity

Politics of technological singularity: timenergy reductionist for possibilities of human emancipation (of their time and energy) made possible by technological automation

Philosophy of Nick Land claims that capitalism is artificial intelligence eroding both human beings and cultural traditions, and that this process should be embraced and accelerated (capitalism saves humanity by destroying it)

Challenge: Land forces Leftist politics to confront the darkest tendencies of capitalism, not just exploitation and domination in capitalism, but the threat of human extinction/automated destruction of the human being themselves

Žižekian critique of Nick Land: accelerationism is too optimistic, presupposes a deterministic future (ideology); philosophical stance: future is inherently unknowable superposition (“quantum history”), politically open for subjectivity

The course as a whole will further dive into the relationship between Land’s Capitalism = Artificial Intelligence, Žižek’s notion of a “Wired Brain”, Žižek’s critique of Nick Land, as well as the relationship between capitalism and timenergy. For the complete course description, schedule, and recommended readings, see:

To join us this October, see:

Good, I.J. 1965. Speculations concerning the first ultraintelligent machine. Advances in Computers, 6: 31-83.

Ibid.

Vinge, V. 1993. The coming technological singularity: how to survive in the post-human era. Vision 21: Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering in the Era of Cyberspace. NASA.

Kurzweil, R. 2005. The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. Penguin. p. 33-34.

Ibid. p. 34.

Why did Stephen Hawking warn the world against AI before his death? The answer is deeply chilling. (link) (accessed: Sept 30 2025).

‘Godfather of AI’ shortens odds of the technology wiping out humanity over next 30 years (link) (accessed: Oct 1 2025).

Last, C. 2020. Global Brain Singularity: Universal History, Future Evolution, and the Humanity’s Dialectical Horizon. Springer.

Ibid. p. 6-64.

Ibid. p. 66-147.

Ibid. p. 150-211.

Ibid. p. 214-316.

Wiener, N. 1966. God & Golem Inc.: A comment on certain points where cybernetics impinges on religion. The M.I.T. Press.

de Garis, H. 2005. The Artilect War: Cosmists Vs. Terrans: A Bitter Controversy Concerning Whether Humanity Should Build Godlike Massively Intelligent Machines. Etc Pubns.

Istvan, Z. 2013. The Transhumanist Wager. Futurity Imagine Media LLC.

Huxley, J. 1951 (2015). Transhumanism. Ethics in Progress 6.1: 12-16.

Fukuyama, F. 2002. Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hughes, J. 2004. Citizen Cyborg: Why democratic societies must respond to the redesigned human of the future. Basic Books.

Rifkin, J. 2014. The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The internet of things, the collaborative commons, and the eclipse of capitalism. Macmillan.

Diamandis, P. & Kotler, S. 2012. Abundance: The future is better than you think. Simon and Schuster.

Ford, M. 2015. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. Simon and Schuster.

Moravec, H. 1988. Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence. Harvard University Press.

Vinge, V. 1993. The coming technological singularity: how to survive in the post-human era. Vision 21: Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering in the Era of Cyberspace. NASA.

Barrat, J. 2013. Our Final Invention: Artificial intelligence and the end of the human era. Hachette.

Kelly, K. 2010. What Technology Wants. Viking Press.

Goertzel, B. 2002. Creating Internet Intelligence: Wild Computing, Distributed Digital Consciousness, and the Emerging Global Brain. Springer Science & Business Media.

Heylighen, F. 2014. Return to Eden? Promises and perils on the road to a global superintelligence. In: The End of the Beginning: Life, Society and Economy on the Brink of the Singularity. p. 243-306.

Tegmark, M. 2017. Life 3.0: Being human in the age of artificial intelligence. Vintage.

Kaku, M. 2014. The Future of Mind: The scientific quest to understand, enhance, and empower the mind. Anchor.

Drexler, E. 2013. Radical Abundance: How a revolution in nanotechnology will change civilization. PublicAffairs.

Kurzweil, R. 2005. The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. Penguin.

Bostrom, N. 2014. Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press.

Land, N. 1987-2007. Critique of Transcendental Miserablism. In: Fanged Noumena: Collective Writings 1987-2007. Urbanomic. p. 623-627.

Žižek, S. 2020. Hegel in a Wired Brain. Bloomsbury.

https://substack.com/@elliotai/note/c-164564286?r=6jttqk